iZNiK

Historically

NICAEA, town, northwestern Turkey. It lies on the

eastern shore of Lake Iznik. Founded in the 4th century BC by the

Macedonian king Antigonus I Monophthalmus, it was an important center in late

Roman and Byzantine times (see Nicaea, councils of; Nicaea, empire of).

The ancient city's Roman and Byzantine ramparts, 14,520 feet (4,426 m) in

circumference, remain. The town was besieged and conquered in 1331 by the

Ottoman Turks, who renamed it Iznik and built the Green Mosque (1378-91).

Iznik's prosperity, which was interrupted by the competing growth of

nearby Istanbul as an Ottoman center after 1453, revived in the 16th century

with the introduction of faience pottery making. Iznik subsequently

became famous for its magnificent tiles, but after the workshops were

transferred to Istanbul c. 1700, Iznik began to decline. Its

economy suffered a further blow with the construction of a major railway

bypassing the town. Today Iznik is a small market town and administrative

center for the surrounding district. Pop. (1980) 13,231.

Historically

NICAEA, town, northwestern Turkey. It lies on the

eastern shore of Lake Iznik. Founded in the 4th century BC by the

Macedonian king Antigonus I Monophthalmus, it was an important center in late

Roman and Byzantine times (see Nicaea, councils of; Nicaea, empire of).

The ancient city's Roman and Byzantine ramparts, 14,520 feet (4,426 m) in

circumference, remain. The town was besieged and conquered in 1331 by the

Ottoman Turks, who renamed it Iznik and built the Green Mosque (1378-91).

Iznik's prosperity, which was interrupted by the competing growth of

nearby Istanbul as an Ottoman center after 1453, revived in the 16th century

with the introduction of faience pottery making. Iznik subsequently

became famous for its magnificent tiles, but after the workshops were

transferred to Istanbul c. 1700, Iznik began to decline. Its

economy suffered a further blow with the construction of a major railway

bypassing the town. Today Iznik is a small market town and administrative

center for the surrounding district. Pop. (1980) 13,231.

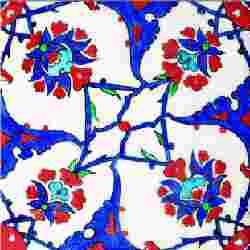

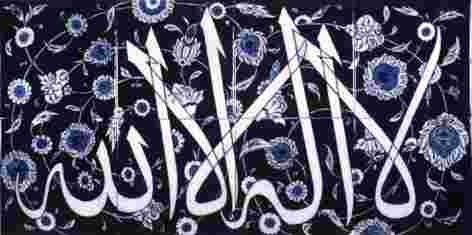

IZNIK WARE:

in Islamic ceramics, a school of Turkish pottery making

that flowered throughout the 16th and on into the 17th century. There may have

been potteries at Iznik, where there were deposits of suitable clay, as

early as the 12th century, but it was not until the late 15th century that

pottery making came into its own in Turkey. The chief center of production

became established in the city of Iznik. Early 16th-century Iznik

wares were influenced by the blue-and-white porcelain of Ming-dynasty China and

by Persian wares. Iznik ware was soft and sandy, being of grayish-white

clay covered with a thin, usually white slip (a mixture of clay and water). Flat

dishes were the commonest shapes, but bowls, jugs, and flower vases were also

made. They were painted with stylized and symmetrical designs of flowers,

leaves, and fruits, along with abstract linear motifs based on these natural

forms and others such as fish scales. By the mid-16th century the range of colors

used in the decoration had expanded from blue and white to include

turquoise, several shades of green, and purple and black. Red had become a

frequently used color by the late 16th century. The quality of Iznik

ware declined in the 17th century, and by 1800 manufacture had ceased.

may have

been potteries at Iznik, where there were deposits of suitable clay, as

early as the 12th century, but it was not until the late 15th century that

pottery making came into its own in Turkey. The chief center of production

became established in the city of Iznik. Early 16th-century Iznik

wares were influenced by the blue-and-white porcelain of Ming-dynasty China and

by Persian wares. Iznik ware was soft and sandy, being of grayish-white

clay covered with a thin, usually white slip (a mixture of clay and water). Flat

dishes were the commonest shapes, but bowls, jugs, and flower vases were also

made. They were painted with stylized and symmetrical designs of flowers,

leaves, and fruits, along with abstract linear motifs based on these natural

forms and others such as fish scales. By the mid-16th century the range of colors

used in the decoration had expanded from blue and white to include

turquoise, several shades of green, and purple and black. Red had become a

frequently used color by the late 16th century. The quality of Iznik

ware declined in the 17th century, and by 1800 manufacture had ceased.

Iznik is

located on the banks of a scenic lake in the province of Bursa in the

northwestern part of Anatolia. In antiquity, the town lay within the borders of

the Bithynian region. According to one legend the town was established

on

the return of the God Dionysus from India.

on

the return of the God Dionysus from India.

Iznik was colonized by the soldiers who escorted Alexander the

Great (356-323 BC) during his conquests. When Antigonas Monophthalmus founded

the city in 316 BC, there was already a settlement of the Bottiaei people there

called Elikore, and Antigonas named the town Antigoneia after himself. Following

the battle of Ipsus (301 BC), one of Alexander's generals, Lysimachos (360-281

BC) took the city and named it Nikaia after his wife and daughter of the

Macedonian leader, Antipatros. Throughout the centuries the name Nikaia went

through phonetic changes, becoming first Nicea and eventually Iznik in Turkish

times.

In the course of its history from 316 BC to present day, Iznik

presents a picture of a city that has undergone great cultural and architectural

changes. In the true sense of the word, Iznik is an archeological and historical

art laboratory of the Romans, Byzantine, Seljuk and Ottoman Turks.

Recent excavations of Iznik kilns tell us that the Ottoman

ceramics in Iznik had a Seljuk background. The latest research and analysis

have revealed that the white pasted hard ceramic consists of the same material

as the soft porcelain used in the Ottoman period. At first, blue and white were the prevailing colors in the pots and wall

tiles in this category. During the 16th century, the Turquoise was introduced.

The embossed red of the wall tiles of the mihrab of Suleymaniye Mosque (1555)

marks the peak of Ottoman tiles and ceramics. During the Ottoman era, the Iznik

tiles and pottery were exported to other countries via the island of Rhodes,

then under Turkish rule.

period. At first, blue and white were the prevailing colors in the pots and wall

tiles in this category. During the 16th century, the Turquoise was introduced.

The embossed red of the wall tiles of the mihrab of Suleymaniye Mosque (1555)

marks the peak of Ottoman tiles and ceramics. During the Ottoman era, the Iznik

tiles and pottery were exported to other countries via the island of Rhodes,

then under Turkish rule.

A famous Turkish traveler, Evliya Celebi, mentions the

existence of 300 workshops in Iznik during the l7th century. This number, also

justified by the excavations, gives us an idea of the importance of tile

production in this town. Various reasons have been put forward with regard to

the decline of tile production in Iznik. The most widely accepted theory is that

the demand from Istanbul (then Constantinople) for the use of these tiles in

major public buildings such as mosques and palaces had fallen during the period

of decline of the Ottoman Empire.

During the Turkish war of Independence, Iznik endured

turbulent times. The town was invaded by Greeks in September 1920, and towards

the final stages of the war, Iznik was burnt to the ground by the defeated

invaders, forcing many inhabitants to flee. With the declaration of the Turkish

Republic, Iznik became home for an influx of Turkish immigrants from Greece and

Thrace.

Iznik became a center of worldwide attention once again when

the year 1989 was declared the year of Iznik. Several activities relating to

Iznik took place; a symposium, an international exhibition and the publication

of several books. The Iznik Foundation was established in September 1993.

The Characteristics of IZNIK Tiles

Iznik Tiles are admired worldwide for the following reasons :

Iznik Tiles are made on a very clean white base with hard backs and under-glaze

decorations in a unique technique.

70-80 percent of an Iznik tile is composed of quartz and

quartzite. Its beauty arises from the harmonious composition of three

successive

quartz layers and a paste-slip-glaze combination that is extremely difficult to

bring together. The mixture of quartz, clay and glaze disperses in a very wide

thermal spectrum at 900 centigrade. After painstaking research, the problem of

the fluctuating thermal behavior of the tiles due to their quartz and rock

crystal composition was solved. The result; a tile made primarily out of a

semi-precious stone, quartz.

successive

quartz layers and a paste-slip-glaze combination that is extremely difficult to

bring together. The mixture of quartz, clay and glaze disperses in a very wide

thermal spectrum at 900 centigrade. After painstaking research, the problem of

the fluctuating thermal behavior of the tiles due to their quartz and rock

crystal composition was solved. The result; a tile made primarily out of a

semi-precious stone, quartz.

Even though it may appear to be against the principle of

"ceramic textural unity", the unique structure of the tiles cause

dilatation in hot, and shrinkage in cold or freezing conditions. Iznik tiles are

extremely durable, and versatile for any decorative or architectural concept.

In Iznik tiles, one can observe colors resembling those of

semi-precious stones such as the dark blue of lapis lazuli, the blue of

turquoise, the redness of coral, and the green of emerald.

Some of the colors observed on the tiles and utensils,

particularly the coral red, are very hard to obtain and apply. To obtain all of

these colors, the cornea white and opaque sheen glazes are required. The

slightly opaque quality of the glaze on the tiles cushions reflective light,

producing a relaxing expression.

The figures on the tiles and utensils reflect allegorical and

symbolic characteristics, namely the flora and fauna of the region. The

geometrical designs can be interpreted cosmologically as a general description

or depiction of the world or the Universe. Iznik Tiles are never overpowering or

overstated, and tend towards a timeless discretion and moderation, blending beautifully with surrounding architecture.

The old masters kept their production techniques very secret,

even from their own families and students. They took production secrets of their

manufacture lay concealed for centuries.

Unlike current ceramic technologies, our production is

fundamentally based on the natural synthesis of its various components. This

intensely difficult ceramic production process is made possible through the

synthesis of human labor, creativity and patience.

IZNIK Tiles Today

Iznik Kiln excavations that have been carried out for over 20 years by

Archeology and history Departments of Istanbul University, gives us clues as to the types of kilns and ceramics used in the Art of Iznik

tile making.

gives us clues as to the types of kilns and ceramics used in the Art of Iznik

tile making.

Excavations have revealed that Iznik tile production was high

on wastage owing to the large proportion of quartz in the ceramic. Therefore,

only through scientific research could a unified Iznik tile concept be formed.

Many experiments with the minerals in the area were carried on in the course of

which thousands of experimental plates were produced only to be broken and

thrown away.

Current outputs are not mere reproductions of 16th Century

masterpieces. Iznik Tiles today are the continuum of the Iznik tradition and

heritage after three centuries. Presently, our end product is equal or better in

terms of quality.

The Iznik Foundation has received the support of scientific

foundations and NGO's such as TUBITAK - MAM (Turkish Scientific Research

Institute - Marmara Research Center, I.T.U. (Istanbul Technical University), I.U.

(Istanbul University), in Turkey, in a vast range of analysis.

Old Iznik tiles reached their heyday in the 16th century, and

the masterpieces produced at that time are regarded as the most valuable

specimens in the art of ceramics by the leading museums of the world. Currently,

Iznik Tiles are used as an architectural element in old and modern buildings by

the discriminating decorators, architects and art lovers.

inventories

in museums and architectural works of old Iznik tiles both in Turkey and abroad,

and to establish a documentation center. Each year the Foundation prepares

calendars with different tile compositions taken from historical buildings and

source documents.

inventories

in museums and architectural works of old Iznik tiles both in Turkey and abroad,

and to establish a documentation center. Each year the Foundation prepares

calendars with different tile compositions taken from historical buildings and

source documents.

![]()

Home | Ana

Sayfa | All About Turkey | Turkiye

hakkindaki Hersey | Turkish Road Map

| Historical Places in Adiyaman | Historical

Places in Turkey | Mt.Nemrut | Slide

Shows | Related Links | Guest

Book | Disclaimer | Send a Postcard | Travelers' Stories | Donate a little to help | Getting Around Istanbul | Adiyaman Forum

|

|