ASPENDOS-PERGE-SIDE

|

|

|

ASPENDOS-PERGE-SIDE

|

Aspendos, located beside the river Eurymedon (Köprüçay), is renowned

throughout the world for its magnificent ancient amphitheatre.

Aspendos, located beside the river Eurymedon (Köprüçay), is renowned

throughout the world for its magnificent ancient amphitheatre.

According to Greek legend, the city was founded by Argive colonists who, under the leadership of the hero Mopsos, came to Pamphylia after the Trojan War. Aspendos was one of the first cities in the region to strike coinage under its own name. On these silver staters dated to the fifth and fourth century B.C., however, the name of the city is written es Estwediiys in the local script. A late eighth century B.C. bilingual inscription carved in both Hittite hieroglyphs and the Phoenician alphabet discovered in the 1947 excavation of Karatepe near Adana, states that Asitawada, the king of Danunum (Adana), founded a city called Azitawadda, a derivation of his own name, and that he was a member of the Muksas, or Mopsus, dynasty. The striking similarity between the names "Estwediiys" and "azitawaddi" suggests the possibility that Aspendos was the city this king founded.

Aspendos did not play an important role in antiquity as a political force. Its political history during the colonization period corresponded to the currents of the Pamphylian region. Within this trend, after the colonial period, it remained for a time under Lycian hegemony. In 546 B.C. it came under Persian domination. The face that the city continued to mint coins in its own name, however, indicates that it had a great deal of freedom even under the Persians.

In 467 B.C. the statesman and military commander Cimon, and his fleet of 200 ships, destroyed the Persian navy based at the mouth of the river Eurymedon in a surprise attack. In order to crush to Persian land forces, he tricked the Persians by sending his best fighters to shore wearing the garments of the hostages he had seized earlier. When they saw these men, the Persians thought that they were compatriots freed by the enemy and arranged festivities in celebration. Taking advantage of this, Cimon landed and annihilated the Persians. Aspendos then became a member of the Attic-Delos Maritime league.

The Persians captured the city again in 411 B.C. and used it as a base. In

389 B.C. the commander of Athens, in an effort to regain some of the prestige

that city had lost in the Peloponnesian Wars, anchored off the coast of Aspendos

in an effort to secure its surrender. Hoping to avoid a new war, the people of

Aspendos collected money among themselves and gave it to the commander,

entreating him to retreat without causing any damage. Even though he took the

money, he had his men trample all the crops in the fields. Enraged, the

Aspendians stabbed and killed the Athenian commander in his tent.

effort to regain some of the prestige

that city had lost in the Peloponnesian Wars, anchored off the coast of Aspendos

in an effort to secure its surrender. Hoping to avoid a new war, the people of

Aspendos collected money among themselves and gave it to the commander,

entreating him to retreat without causing any damage. Even though he took the

money, he had his men trample all the crops in the fields. Enraged, the

Aspendians stabbed and killed the Athenian commander in his tent.

When Alexander the Great marched into Aspendos in 333 B.C. after capturing Perge, the citizens sent envoys to him to request that he would not establish that he be given the taxes and horses that they had formerly paid as tribute to the Persian king. After reaching this agreement. Alexander went to Side, leaving a garrison there on the city's surrender. Going back through Sillyon, he learned that the Aspendians had failed to ratify the agreement their envoys had proposed and were preparing to defend themselves. Alexander marched to the city immediately. When they saw Alexander returning with his troops, the Aspendians, who had retreated to their acropolis, again sent envoys to sue for peace. This time, however, they had to agree to very harsh terms; a Macedonian garrison would remain in the city and 100 gold talents as well as 4.000 horses would be given in tax annually.

During the wars that followed the death of Alexander, the city came alternately under the control of the Ptolemies and the Seleucids, later falling into the hands of the Kingdom of Pergamum, to which it remained bound until 133 B.C.

From Cicero's presentation of the case before the Roman senate, we know that in 79 B.C. Gaius Verres, the questor of Cilicia, pillaged Aspendos just as he had Perge. Verres, right in front of the citizens, took statues from the temples and squares and had them loaded into carts. He even had Aspendos famous statue of a harpist set up in his own home.

Aspendos, like most of the other Pamphylian cities, reached its height in the

second and third centuries A.D. Most of the monumental architecture still

visible here today dates to this golden age. Although the city was not on the

coast, the river Eurymedon, on whose banks it was situated, allowed ships to

reach it. This accessibility, together with the productive plain and the thickly

forested mountains that lay behind Aspendos, were major factors in its

development. Gold and silver embroidered tapestries woven in the city, furniture

and figurines made from the wood of lemon trees, salt obtained from nearby Lake

Capria, wine, and especially the famous horses of Aspendos were its foremost

exports. Although they were renowned as grape growers and wine merchants, they

did not offer wine to their gods in their religious rites. They explained this

omission by saying that if wine were reserved for the gods, birds would not have

the courage to eat grapes.

Aspendos, like most of the other Pamphylian cities, reached its height in the

second and third centuries A.D. Most of the monumental architecture still

visible here today dates to this golden age. Although the city was not on the

coast, the river Eurymedon, on whose banks it was situated, allowed ships to

reach it. This accessibility, together with the productive plain and the thickly

forested mountains that lay behind Aspendos, were major factors in its

development. Gold and silver embroidered tapestries woven in the city, furniture

and figurines made from the wood of lemon trees, salt obtained from nearby Lake

Capria, wine, and especially the famous horses of Aspendos were its foremost

exports. Although they were renowned as grape growers and wine merchants, they

did not offer wine to their gods in their religious rites. They explained this

omission by saying that if wine were reserved for the gods, birds would not have

the courage to eat grapes.

Few Aspendians made a name for themselves in history. Andromachos was a famous military commander in his day and was also the governor of Phoenicia and Syria. Little is known of the work of the native philosopher Diodorus, but that he wore the long hair, dirty clothes, and bare feet of the Cynics, which suggests he was influenced by Pythagorus.

At the beginning of the thirteenth century, Aspendos began to bear the imprint of settlement by the Seljuk Turks, especially during the reign of Alaeddin Keykubat I, when the theatre was thoroughly restored, embellished in Seljuk style with elegant tiles, and used as a palace.

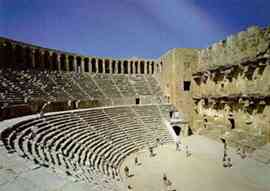

At the end of the road that turns off the Antalya -Alanya highway, we come to

the most magnificent, as well as functionally the best resolved and most

complete example of a Roman theatre. The building, faithful to the Greek

tradition, is partially built into the slope of a hill. Today visitors enter the

stage building via a door opened in the facade during a much later period. The

original entrances, however, are the vaulted paradoses at both ends of the stage

building. The cavea is semicircular in shape and divided in two by a large

diazoma. There are 21 tiers of seats above and 20 below. To provide ease of

circulation so that the spectators could reach their seats without difficulty,

radiating stairways were built, 10 in the lower level starting at the orchestra

and 21 in the upper beginning at the diazoma. A wide gallery consisting of 59

arches and thought to have been built at a later date, goes from one end of the

upper cavea to the other. From an architectural point of view, the diazoma's

vaulted gallery acts as a substructure supporting the upper cavea. As a general

rule of protocol, the private boxes above the entrances on both sides of the

cavea were reserved for the Imperial family and the vestal virgins. Beginning

from the orchestra and going up, the first row of seats belonged to senators,

judges, and ambassadors, while the second was reserved for other notables of the

city. The remaining sections were open to all the citizens. The women usually

sat on the upper rows under the gallery. From the names carved on certain seats

in the upper cavea, it is clear that these too were reserved. Although it is

impossible to determine the exact seating capacity of the theatre, it is said to

have seated between 10,000 and 12,000 people. In recent years, concerts given in

the theatre as part of the Antalya Film and Art Festival, have shown that as

many as 20,000 spectators can be crowded into the seating area.

family and the vestal virgins. Beginning

from the orchestra and going up, the first row of seats belonged to senators,

judges, and ambassadors, while the second was reserved for other notables of the

city. The remaining sections were open to all the citizens. The women usually

sat on the upper rows under the gallery. From the names carved on certain seats

in the upper cavea, it is clear that these too were reserved. Although it is

impossible to determine the exact seating capacity of the theatre, it is said to

have seated between 10,000 and 12,000 people. In recent years, concerts given in

the theatre as part of the Antalya Film and Art Festival, have shown that as

many as 20,000 spectators can be crowded into the seating area.

Without doubt the Aspendos theatre's most striking component is the stage building. On the lower floor of this two-storey structure, which is built of conglomerate rock, were five doors providing the actors entrance to the stage. The large door at the centre was known as the porta regia, and the two smaller ones on either side as the porta hospitales. The small doors at orchestra level belong to long corridors leading to the areas where the wild animals were kept. From surviving fragments it appears that sculptural works were placed in niches and aedicula under triangular and semicircular pediments.

In the pediment at the centre of the colonnaded upper floor is a relief of Dionysos, the god of wine and the founder and patron of theatres. Red zigzag motifs against white plaster, visible on some portions of the stage building, date to the Seljuk period. The top of the stage building is covered with a highly ornamented wooden roof.

The theatre at Aspendos is also famous for its magnificent accoustics. Even

the sligtest sound made at the centre of the orchestra can be easily hear as far

as the uppermost galleries. Anatolia's patricians, who lived in the midst of a

rich cultural heritage, created stories connected with the cities and monuments

around them. One of these tales which has been passed down from generation to

generation is about Aspendos' theatre. The king of Aspendos proclaimed that he

would hold a contest to see what man could render the greatest service to the

city; the winner would marry the king's

daughter. Hearing this, the artisans of

the city began to work at high speed. At last, when the day of the decision came

and the king had examined all their efforts one by one, he designated two

candidates. The first of them had succeeded in setting up a system that enabled

water to be brought to the city from great distances via aqueducts. The second

built the theatre. Just as the king was on the point of deciding in favour of

the first candidate, he was asked to have one more look at the theatre. While he

was wandering about in the upper galleries, a deep voice from an unknown source

out saying again and again, "The king's daughter must be given to me"

. In astonishment the king looked around for the owner of the voice but could

find no one. It was, of course, the architect himself, proud of the accoustical

masterpiece he had created, who was speaking in a low voice from the stage. In

the end, it was the architect who won the beautiful girl and the wedding

ceremony took place in the theatre.

daughter. Hearing this, the artisans of

the city began to work at high speed. At last, when the day of the decision came

and the king had examined all their efforts one by one, he designated two

candidates. The first of them had succeeded in setting up a system that enabled

water to be brought to the city from great distances via aqueducts. The second

built the theatre. Just as the king was on the point of deciding in favour of

the first candidate, he was asked to have one more look at the theatre. While he

was wandering about in the upper galleries, a deep voice from an unknown source

out saying again and again, "The king's daughter must be given to me"

. In astonishment the king looked around for the owner of the voice but could

find no one. It was, of course, the architect himself, proud of the accoustical

masterpiece he had created, who was speaking in a low voice from the stage. In

the end, it was the architect who won the beautiful girl and the wedding

ceremony took place in the theatre.

We know from an inscription in the southern parados that the theatre was constructed during the reign of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius (161-180 A.D.) by the architect Zeno, the son of an Aspendian named Theodoros. According to the inscription, the people of Aspendos, out of admiration for Zeno, awarded him a large garden beside the stadium. Greek and Latin inscriptions above the entrances on both sides of the stage building tell us that, two brothers named Curtius Crispinus and Curtius Auspicatus commissioned the building and dedicated it to the gods and the Imperial family.

No fee was charged for putting on a performance in the theatre. A portion of

the necessary production costs were covered by civic institutions, but after the

performance, part of the profits was turned over to these organizations.

Generally one had to pay a fee or buy tickets to gain entry to plays or

competitions. Tickets were made of metal, ivory, bone, or in most cases, fired

clay, with a picture on one side and a row and seat number on the other.

covered by civic institutions, but after the

performance, part of the profits was turned over to these organizations.

Generally one had to pay a fee or buy tickets to gain entry to plays or

competitions. Tickets were made of metal, ivory, bone, or in most cases, fired

clay, with a picture on one side and a row and seat number on the other.

Aspendos' other principal remains are above the acropolis, behind the theatre. The first building one comes to on the acropolis, which is reached via a footpath starting alongside the theatre, is a basilica measuring 27x105 metres. The basilica is an architectural from invented by the Romans. Roman basilicas were used for a wide wariety of purposes, but these were all concerned with public affairs. Markets and law courts were set up in buildings. The basilica plan consists of a large central hall surrounded by smaller chambers. The central hall is separated from those at the sides by columns and its roof is higher. İnside the basilica is a tribunal. During the Byzantine era the building underwent major alterations and lost much of its original character.

South of the basilica and bounded on three sides by houses, is the agora, the

centre of the city's commercial, social, and political activities. A little

further to the west are twelve shops of equal size all in a line at the rear of

a stoa.

South of the basilica and bounded on three sides by houses, is the agora, the

centre of the city's commercial, social, and political activities. A little

further to the west are twelve shops of equal size all in a line at the rear of

a stoa.

North of the agora is a nymphaeum of which only the front wall remains standing. Measuring 32.5 m. in width by 15 m. in height, this two-level facade has five niches at each level. The middle niche in the lower level is larger than the others and is thought have been used as a door. It is clear from the marble bases at the foot of the wall that the building originally had a colonnaded facade.

Behind the nymphaeum is a building of unusual plan, either an odeon or a bouleuterion where council members met.

Another of Aspendos' remains that should not be missed is its aqueduct. This one kilometre-long series of arches which brought water to the city from the mountains at the north, represents an extraordinary feat of engineering and is one of the rare examples surviving antiquity. The water was brought from ist source in a channel formed by hollowed stone blocks on top of 15 metre-high arches. Near both ends of the aqueduct the water was collected in towers some 30 metres high, which was distributed to the city.

An inscription found in Aspendos tells us that a certain Tiberius Claudius Italicus had the aqueduct built, and presented it to the city. Its architectural features and construction techniques date it to the middle of the second century A.D.

Greek ASPENDOS, modern BELKIS,

ancient city of Pamphylia, now in southwestern Turkey. It is noted for its Roman ruins. A wide range of coinage from the 5th century BC onward attests to the

city's wealth. Aspendus was occupied by Alexander the Great in 333 BC and later

passed from Pergamene to Roman rule in 133 BC. According to Cicero, it was

plundered of many of its artistic treasures by the provincial governor Verres.

The hilltop ruins of the city include a basilica, an agora, and some rock-cut

tombs of Phrygian design. A huge theatre, one of the finest in the world, is

carved out of the northeast flank of the hill. It was designed by the Roman

architect Zeno in honour of the emperor Marcus Aurelius (reigned AD 161-180)

ruins. A wide range of coinage from the 5th century BC onward attests to the

city's wealth. Aspendus was occupied by Alexander the Great in 333 BC and later

passed from Pergamene to Roman rule in 133 BC. According to Cicero, it was

plundered of many of its artistic treasures by the provincial governor Verres.

The hilltop ruins of the city include a basilica, an agora, and some rock-cut

tombs of Phrygian design. A huge theatre, one of the finest in the world, is

carved out of the northeast flank of the hill. It was designed by the Roman

architect Zeno in honour of the emperor Marcus Aurelius (reigned AD 161-180)

The present-day Belkiz was once situated on the banks of the River Eurymedon, now known as the Kopru Cay. In ancient times it was navigable; in fact, according to Strabo, the Persians anchored their ships there in 468 B.C., before the epic battle against the Delian Confederation.

It is commonly believed that Aspendos was founded by colonists from Argos. One thing is certain: right from the beginning of the 5th century, Aspendos and Side were the only two towns to mint coins. An important river trading port, it was occupied by Alexander the Great in 333 B.C. because it refused to pay tribute to the Macedonian king. It became an ally of Rome after the Battle of Sipylum in 190 B.C. and entered the Roman Empire.

The town is built against two hills: on the "great hill" or Buyuk

Tepe stood the acropolis, with the agora, basilica, nymphaeum and bouleuterion

or "council chamber". Of all these buildings, which were the very hub

of the town, only ruins remain. About one kilometer north of the town, one can

still see the remains of the Roman aqueduct that supplied Aspendos with water, transporting it from a distance

of over twenty kilometers, and which still maintains its original height.

The town is built against two hills: on the "great hill" or Buyuk

Tepe stood the acropolis, with the agora, basilica, nymphaeum and bouleuterion

or "council chamber". Of all these buildings, which were the very hub

of the town, only ruins remain. About one kilometer north of the town, one can

still see the remains of the Roman aqueduct that supplied Aspendos with water, transporting it from a distance

of over twenty kilometers, and which still maintains its original height.

Aspendos' theatre is the best preserved Roman theatre anywhere in

Turkey. It was designed during the 2nd century A.D. by the architect Zeno, son

of Theodore and originally from Aspendos. Its two benefactors— the brothers

Curtius Crispinus and Curtius Auspicatus —dedicated it to the Imperial family

as can be seen from certain engravings on the stones. Discovered in 1871 by

Count Landskonski during one of his trips to the region, the theatre is in

excellent condition thanks to the top quality of the calcareous stone and to the

fact that the Seljuks turned it into a palace, reinforcing the entire north wing with bricks. Its thirty-nine tiers of steps—96

meters long—could seat about twenty thousand spectators. At the top, the

elegant gallery and covered arcade sheltered spectators. One is immediately

struck by the integrity and architectural distinction of the stage building,

consisting of a Irons scacnae which opens with five doors onto the proscenium

and

scanned by two orders of windows which also project onto the outside wall.

There is an amusing anecdote about the construction of this theatre—in which

numerous plays are still held, given its formidable acoustics — and the

aqueduct just outside the town: in ancient times, the King

of Aspendos had a daughter of rare beauty named Semiramis, contended by two

architects; the king decided to marry her off to the one who built an important

public work in the shortest space of time. The two suitors thus got down to work

and completed two public works at the same time: the theatre and the aquaduct.

As the sovereign liked both buildings, he thought it right and just to divide

his daughter in half. Whereas the designer of the aquaduct accepted the

Solomonic division, the other preferred to grant the princess wholly to her

rival. In this way, the sovereign understood that the designer of the theatre

had not only built a magnificent theatre— which was the pride of the town—,

but would also be an excellent husband to his daughter; consequently he granted

him her hand in marriage.

amusing anecdote about the construction of this theatre—in which

numerous plays are still held, given its formidable acoustics — and the

aqueduct just outside the town: in ancient times, the King

of Aspendos had a daughter of rare beauty named Semiramis, contended by two

architects; the king decided to marry her off to the one who built an important

public work in the shortest space of time. The two suitors thus got down to work

and completed two public works at the same time: the theatre and the aquaduct.

As the sovereign liked both buildings, he thought it right and just to divide

his daughter in half. Whereas the designer of the aquaduct accepted the

Solomonic division, the other preferred to grant the princess wholly to her

rival. In this way, the sovereign understood that the designer of the theatre

had not only built a magnificent theatre— which was the pride of the town—,

but would also be an excellent husband to his daughter; consequently he granted

him her hand in marriage.

PERGE

Perge,

one of Pamphylia's foremost cities, was founded on a wide plain between two

hills 4 km. west of the Kestros (Aksu) river.

Perge,

one of Pamphylia's foremost cities, was founded on a wide plain between two

hills 4 km. west of the Kestros (Aksu) river.

Skylax, who lived in the fourth century B.C. and was the earliest of the ancient writers to mention Perge, states that the city was in Pamphylia. In the New Testament book, Acts of the Apostles, the sentence "...when Paul and his company loosed from Paphos, they came to Perge in Pamphylia" suggests that Perge could be reached from the sea in ancient times. Just as the Kestros provides convenient communication today, the diver also played an important role in antiquity, making the land productive, and securing for Perge the possibility of sea trade. Despite its being some 12 km. inland from the sea, Perge by means of the Kestros, was able to benefit from the advantages of the sea as if it were a coastal city. Moreover, it was removed from the attacks of pirates invading by sea.

In later copies of a third or fourth century map of the world, Perge is shown

beside the principal road starting at Pergamum and ending at Side.

Pergamum and ending at Side.

According to Strabo, the city was founded after the Trojan War by colonists from Argos under the leadership of heroes named Mopsos and Calchas. Linguistic research confirms that Achaeans entered Pamphylia toward the end of the second millennium B.C. ın addition to these studies, inscriptions dating to 120-121 A.D., discovered in the 1953 excavations in the courtyard of Perge's Hellenistic city gate, provide further testimony to this colonization; inscriptions on statue bases mention the names of seven heroes-Mopsos, Calchas, Riksos, Labos, Machaon, Leonteus, and Minyasas, the legendary founders of the city.

There

is no further record of Perge in written sources until the middle of the fourth

century. There can be no doubt, however, that Perge was also under Persian rule

until the arrival of Alexander the Great.

There

is no further record of Perge in written sources until the middle of the fourth

century. There can be no doubt, however, that Perge was also under Persian rule

until the arrival of Alexander the Great.

In 333 B.C. Perge surrendered to Alexander without resistance. Its submissive behaviour can be explained by, besides its favourable policy, the fact that at this period the city was not yet surrounded by protective walls.

With the death of Alexander, Perge remained for a short time within the boundaries of Antigonos domain and later fell under Seleucid sovereignty. When the border dispute between the Seleucids and the king of Pergamum continued after the treaty of Apamea, the Roman consul Manlius Vulso was sent from Rome in 188 A.D. in the capacity of mediator. Learning that Antiochos III had a garrison in Perge, he surrounded the city at the urging of Pergamum's king. At this point the garrison commander informed the consul that he could not surrender the city before obtaining permission from Antiochos; for this, he said he would need thirty days, at the end of which, Perge passed to Pergamum.

Perge became totally independent when the kingdom of Pergamum was turned over

to Rome in about 133 B.C.

In 79 B.C. the Roman statesman Cicero described to the senate, Cilician questor Gaius Verres' unlawful conduct in Perge, saying, "As you know, there is a very old and sacred temple to Diana in Perge. I assert that this was also robbed and looted by Verres and that the gold was stripped from the statue of Diana and stolen".

Artemis occupied an important position among the gods and gooddesses held sacred in Perge. This ancient Anatolian goddess appears on Hellenistic coins under the name Vanassa Preiia, as she was called in the Pamphylian dialect; after Greek colonization she became known as Artemis Pergaia. Besides being rendered on coinage as a cult statue or as a huntress, the Artemis of Perge is the subject of a variety of statues and reliefs found in excavations of the city. A relief in the from of a cult statue on a square stone block is particularly interesting. The cult of Artemis Pergaia also appears in many other cities, even in countries around the Mediterranean.

As famous as Artemis Pergaia was in the ancient world, no trace of the temple has yet been found. For the present we must content ourselves with what knowledge we can get from schematic representations of the temple on coins; of this renowned monument that safeguarded the gold-adorned statue of Artemis, and whose scale, beauty, and construction was marvelled at by ancient writers.

In 46 A.D., Perge became the setting of an event important to the Christian world. The New Testament book, the Acts of the Apostles, writes that St. Paul journeyed from Cyprus to Perge, from there continued on to Antiocheia in Pisidia, then returned to Perge where he delivered a ser mon. Then he left the city and went to Attaleia.

From the beginning of the Imperial era, work projects were carried out in Perge, and in the second and third centuries A.D., the city grew into one of the most beautiful, not just in Pamphylia, but in all of Anatolia.

In the first half of the fourth century, during the reign of Constantine the Great (324-337), Perge became an important centre of Christianity once this faith had became of official religion of the Roman Empire. The city retained its status as a Christian centre in the fifth and sixth centuries. Due to frequent rebellions and raids, the citizens retreated inside the city walls, able to defend themselves only from within the acropolis. Perge lost its remaining power in the wake of the mid-seventh century Arab raids. At this time some residents of the city migrated to Antalya.

The first building one encounters on entering the city is a theatre of Greco-Roman type constructed on the southern slopes of the Kocabelen hill. The cavea, slightly more than a semicircle, is divided in two by a wide diazoma passing through it. It contains 19 seating levels below and 23 above, which translate into a total seating capacity of about 13,000. In conformance to the canons of Roman theatre galleries serving as the entrance and exit ways, spectators reached the diazoma from the parados on either side via vaulted passages and stairs; from there they were dispersed to their seats.

The orchestra, situated between the cavea and the stage building, is wider than a semicircle. Because of the gladiatorial and will animal combats popular in the mid-third century, the orchestra was used as an arena. To keep the animals from escaping, it was surrounded by carved balustrade panels that passed between marble knobs made in the form of Herme.

The

partially standing two-storey stage building can be dated to the middle of the

second century A.D. by its columned architecture and sculptural ornamentation.

On the facade, columns between the five doors by which the actors entered and

exited support a narrow podium above. The theatre's most striking feature is a

series of marble reliefs of mythological subject decorating the face of this

podium. The first relief on the right portrays the local god personifying the

Kestros (Aksu) river, Perge's lifeblood, along with one of the mythological

females called nymphs. From here on, the reliefs depict, in serial form, the

entire life story of Dionysos, the god of wine and the founder and protector of

theatres. Dionysos was the son of Zeus and Semele, the daughter of a king and

reputed to be as beautiful as spring. Hera, ever jealous of her husband, wanted

to get rid of Semele along with her son. To trick her, the goddess assumed the

form of the girl's mother and begged Semele to persuade Zeus to let her see him

in all his might and glory. The credulous Semele was taken in by the ruse and

implored Zeus to acquiesce. Zeus, unable to resist the pleas of his beloved,

came down from Olympos on his golden chariot and appeared before her, but the

mortal Semele could not withstand his radiance and was consumed by fire. Dying,

she gave birth to the fruit of her love, who had not yet come to full term, and

threw him from the flames. Zeus took this little boy, sewed him into his hip and

kept him there until his term was completed. It is in this way that the boy was

given the name Dionysos-born once from his mother's womb and coming into the

world a second time from his father's hip. So that the infant could be protected

from Hera's malevolence, fed and brought to manhood, he was taken by Hermes to

the nymphs of Mount Nysa, who raised the boy in a cave, giving him love and

careful attention. Finally, as a young man, Dionysos one day drank the juice of

all the grapes on the vine growing along the cave's walls. This is how wine was

discovered. With the aim of introducing his new drink into every corner of the

globe and spreading the knowledge of viniculture, the god of wine went on a

journey around the world in a chariot drawn by two panthers.

The

partially standing two-storey stage building can be dated to the middle of the

second century A.D. by its columned architecture and sculptural ornamentation.

On the facade, columns between the five doors by which the actors entered and

exited support a narrow podium above. The theatre's most striking feature is a

series of marble reliefs of mythological subject decorating the face of this

podium. The first relief on the right portrays the local god personifying the

Kestros (Aksu) river, Perge's lifeblood, along with one of the mythological

females called nymphs. From here on, the reliefs depict, in serial form, the

entire life story of Dionysos, the god of wine and the founder and protector of

theatres. Dionysos was the son of Zeus and Semele, the daughter of a king and

reputed to be as beautiful as spring. Hera, ever jealous of her husband, wanted

to get rid of Semele along with her son. To trick her, the goddess assumed the

form of the girl's mother and begged Semele to persuade Zeus to let her see him

in all his might and glory. The credulous Semele was taken in by the ruse and

implored Zeus to acquiesce. Zeus, unable to resist the pleas of his beloved,

came down from Olympos on his golden chariot and appeared before her, but the

mortal Semele could not withstand his radiance and was consumed by fire. Dying,

she gave birth to the fruit of her love, who had not yet come to full term, and

threw him from the flames. Zeus took this little boy, sewed him into his hip and

kept him there until his term was completed. It is in this way that the boy was

given the name Dionysos-born once from his mother's womb and coming into the

world a second time from his father's hip. So that the infant could be protected

from Hera's malevolence, fed and brought to manhood, he was taken by Hermes to

the nymphs of Mount Nysa, who raised the boy in a cave, giving him love and

careful attention. Finally, as a young man, Dionysos one day drank the juice of

all the grapes on the vine growing along the cave's walls. This is how wine was

discovered. With the aim of introducing his new drink into every corner of the

globe and spreading the knowledge of viniculture, the god of wine went on a

journey around the world in a chariot drawn by two panthers.

It is unfortunate that an important section of these beautiful reliefs was damaged as a result of the subsidence of the stage building. From pieces recovered during excavations begun in 1985, it is evident that the building was originally decorated with several more friezes on different themes. The subject of a 5 metre-long frieze from an as yet undetermined part of the building is especially interesting. Here, Tyche holds a cornucopia in her left hand, and in her right a cult statue. On either side are the figures of an old man and two youths bringing bulls for sacrifice to the goddess.

On the right of the asphalt road running from the theatre to the city is one of the best preserved stadiums to have survived from ancient times to our own. This huge rectangular building measuring 34x 334 metres, is shaped like a horseshoe on its north end and open on its south. It is wery likely that the building was entered at this point via a monumental wooden door. The stadium was built on a substructure of 70 vaulted chambers, 30 along each long side and 10 on its narrow northern end. These chambers are interconnected, with every third compartment providing entrance to the theatre. From inscriptions over the remaining compartments giving the names of their owners and listing various types of goods,it is clear that these spaces were used as shops. The tiers of seats which lie on top of these vaulted rooms, provided a seating capacity of 12,000. When gladiatorial and wild animal combat became popular in the mid-third century, the north end of the stadium was surrounded with a protective balustrade and turned into an arena. Its architectural style and stone work date this edifice to the second century A.D.

Another noteworthy ruin outside the city walls is the tomb of Plancia Magna, who was the daughter of Plancius Verus, the Governor of Bithynia. She was a wealthy and civic minded woman who, around the beginning of works in Perge, and who had a number of spots in the city adorned with monuments and sculpture. Because of her community service, the people, assembly, and senate erected statues of her. In various inscriptions Plancia's name appears with the title "demiurgos", which was the highest civil servant in the city's government. In addition, she was a priestess of Artemis Pergaia, a priestess-for-life of the mother of the gods, and the head priestess of the cult of the emperor.

A large part of Perge is encircled by walls that in some places go back to the Hellenistic period. Towers 12-13 metres high were built on top of the fortifications. However, during the time of the Pax Romana, which provided a period of continuous peace and tranquility, the walls lost their importance, and buildings such as the theatre and stadium could be built beyond the walls without fear. On entering the city through a late period gate in the fourth century walls, one comes to a small rectangular court 40 metres long bounded by walls of later date. From this courtyard one continues through a second, southern gate built in the form of a triumphal arch and highly decorated, particularly on the back. This gate leads into a trapezoidal courtyard 92 metres long and 46 metres wide. On the west wall of this court, which was used as a ceremonial site during the reign of Emperor Septimius Severus (193-211 A.D.) is a monumental fountain or nymphaeum. The building consists of a wide pool, and behind it a two-storeyed richly worked facade. From its inscription, it is apparent that the structure was dedicated to Artemis Pergaia, Septimius Severus and his wife Julia Domna, and their sons. An inscription belonging to the facade, various facade fragments, and marble statues of Septimius Severus and his wife, all found in excavations of the nymphaeum, are now in the Antalya Museum.

A monumental propylon directly north of the nymhaeum opens onto the largest and most magnificent bath in Pamphylia. A large pool (natacia) measuring 13x20 m. covers the inside of an apsed chamber on the south portico of a broad palaestra; the palaestra is bounded in front by a portico. Pergaians cleansed themselves in this pool after exercising in the palaestra. It is clear from the dynamic architecture of the facade, the coloured marble facing, and the statues of Genius, Heracles, Hygiea, Asklepios and Nemesis, that decorated, this space must have been dazzlingly beautiful. From here another door leads to the frigidarium, a space that also contained a pool. Before entering, bathers washed their feet in water flowing along a shallow channel running the full length of the pool's north side. Existing evidence suggests that the frigidarium was adorned with statues of the Muses. Next are the tepidarium and the caldarium, which connect with each other. Beneath these rooms one can see courses of bricks belonging tothe hypocaust system that circulated the hot air coming from the boiler room. Washing in a Roman bath was a proces that took place in several stages. First the bather removed his clothign in a room called the apodyterium and from there entered the palaestra where he took his exercise. Then he either went into the pool to get rid of the dirt and perspiration from this physical exertion, or washed himself in hot water in the caldarium. From there he went to the tepidarium or to the frigidarium for a cold water bath. In the Roman era the bath was not just a place for washing, but was also a place where men met to pass the time of day or to discuss a variety of important topics. The long rectangular compartment at the north of the frigidarium was probably a place where bathers strolled and chatted. A long marble bench extends along this room's west wall. Inscriptions on a large number of plinths found during excavations, indicate the statues that once stood on them were donated by a man named Claudius Peison.

At the northern end of the inner court is a Hellenistic gate that is Perge's

most magnificent structure. Dating to the third century B.C., this gate, consisting of two towers with a horseshoe-shaped court

behind them, was clevery designed according to the defensive strategy of the

day. The towers had three storeys and were covered with a conical roof. With the

aid of Plancia Magna, several alterations in the decoration of the court were

made between 120 and 122 A.D., changing it from a defensive structure to a court

of honour. To create a facade, the Hellenistic walls were covered with slabs of

coloured marble, several new niches were opened, and Corinthian columns were

added. Figures of gods and goddesses like Aphrodite, Hermes, Pan and the

Dioskouroi occupied the niches on the lower level. In excavations in the court,

the inscribed bases of nine statues were found, but the statues themselves have

not been recovered. According to their inscriptions, these statues which must

have been placed in the niches on the upper level, represent the legendary

heroes who founded Perge after the Trojan War, as described in historical notes.

In inscriptions on two pedestals, the names M. Plancius Varus and C. Plancius

Varus, his son, appear with the adjective meaning "founder",

essentially, because of their goodness and generosity toward Perge, they were

acepted as second founders for whom this honour seemed appropriate.

century B.C., this gate, consisting of two towers with a horseshoe-shaped court

behind them, was clevery designed according to the defensive strategy of the

day. The towers had three storeys and were covered with a conical roof. With the

aid of Plancia Magna, several alterations in the decoration of the court were

made between 120 and 122 A.D., changing it from a defensive structure to a court

of honour. To create a facade, the Hellenistic walls were covered with slabs of

coloured marble, several new niches were opened, and Corinthian columns were

added. Figures of gods and goddesses like Aphrodite, Hermes, Pan and the

Dioskouroi occupied the niches on the lower level. In excavations in the court,

the inscribed bases of nine statues were found, but the statues themselves have

not been recovered. According to their inscriptions, these statues which must

have been placed in the niches on the upper level, represent the legendary

heroes who founded Perge after the Trojan War, as described in historical notes.

In inscriptions on two pedestals, the names M. Plancius Varus and C. Plancius

Varus, his son, appear with the adjective meaning "founder",

essentially, because of their goodness and generosity toward Perge, they were

acepted as second founders for whom this honour seemed appropriate.

The horseshoe-shaped court is bounded on the north by a three-arched monumental gate built by Plancia Magna. Inscriptions on pedestals unearthed in excavations indicate that statues of the emperors and their wives from the reign of Nerva to Hadrian, stood in the gate's niches.

An agora 65 metres square is located to the east of the Hellenistic gate. On all four sides a wide stoa surrounds a central lined with shops. The floor of these shops is paved with coloured mosaics. An interesting stone used in an ancient game can be seen in front of one store in the north portico. The game, which was played with six stones per person and thrown like dice, must have been very popular throughout the region, as similar stones were also found in other neighbouring cities. At the centre of the court is a round building, just as there is in Side's agora; the precise nature of this structure is not yet known.

A colonnaded street runs north-south through the city centre going under the triumphal arch of Demetrios-Apollonios, currently under restoration, at a point near the acropolis. This thoroughfare is intersected by another running east-west. On both sides of this 250 metre-long street are broad porticoes behind which are rows of shops. In this way the columned architecture on both sides offers various examples of the Roman understanding of perspective. The porticoes also provided a place where people could both take shelter from the violent rains in winter, and protect themselves from Perge's extremely hot summer sun. Because of their suitability for the climate, avenues of this type are frequently found in the cities of southern and western Anatolia. Certainly the most interesting aspect of Perge's colonnaded street is the pool-like water channel that divides the road down tha middle. Made to flow by the rived god Kestros, these clear, clean waters ran out of a monumental fountain (nymphaeum) at the north end of the street and flowed placidly along the channels, cooling the Pergeians just a little in the cruel Pamphylian heat. At approximately the middle of the street, four relief-carved columns belonging to the portico immediately catch the eye. On the first column, Apollo is depicted riding a chariot drawn by four horses; on the second is Artemis the huntress; the third shows Calchas, one of the city's mythical founders; and the last, Tyche (Fortune).

The main road comes to an end at another nymphaeum built at the foot of the acropolis in the second century A.D. The rich architecture of its two-tiered facade and its numerous statues make it one of Perge's most striking monuments. The water brought from the spring empties into a pool beneath the statue of the river god Kestros standing precisely in the centre of the fountain, and from there flows to the streets via channels.

Turning left from the triumphal arch of Apollonios that intersects the streets, and passing the Hellenistic gate, one comes to the palaestra, known to be Perge's oldest building. Here, under the supervision of their teachers, the youth of the city practised wrestling and underwent physical education. According to an inscription this square edifice, consisting of an open area surrounded by rooms, was dedicated to the Emperor Claudius (reigned 41-54 A.D.) by a certain C. Julius Cornutus.

Perge, transformed by artisans into a city of marble, was truly magnificent, with a faultless layout that would have been the envy of modern city planners. In order to fully appreciate its grandeur today, one must visit the Antalya Museum to see the hundreds of sculptures from Perge now housed there.

Among the famous men raised in this city can be cited the physician Asklepiades, the sophist Varus, and the mathematician Apollonios.

Perge has been under excavation by Turkish archaeologists since 1946.

SILLYON

About 35 km. along the Antalya-Alanya highway, you turn north and continue 8 km. until Silyon is reached. It was built on an ellipse-shaped table-like plateau rising above the flat plain. Due to its location the surrounding areas can easily be seen, and in fact the view stretches as far as the Mediterranean. It was settled in the 4th century B.C. and it lived not only through the Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine periods, but was also used by the Seljuks who also added buildings and increased its wealth. Some of its interesting sights are the stadium, gymnasium, turrets, Seljuk mosque, the theater whose proscenium is buried under rocks, and the sports arena

This

Pamphylian town, located between Perge and Aspendos, is situated on top of a

flat-topped hill with almost vertical flanks. With its unusual physical

formation, the hill is easily recognizable even from a distance. Strabo mentions

in his writings that the city, some 40 stad or 7.2 km, inland, was visible from

Perge.

This

Pamphylian town, located between Perge and Aspendos, is situated on top of a

flat-topped hill with almost vertical flanks. With its unusual physical

formation, the hill is easily recognizable even from a distance. Strabo mentions

in his writings that the city, some 40 stad or 7.2 km, inland, was visible from

Perge.

It is generally accepted that Sillyon, like other cities in Pamphylia, was founded after the Trojan War by the heroes Mopsos and Calchas. A statue base found in Sillyon bears Mopsos' name.

Sillyon began to mint coinage in its own name in the third century B.C. On these coins the name of the city was written as Sylviys, which must have been changed to Sillyon in the Roman era.

The name Sillyon is almost never mentioned in history except, for its appearance in Arrianos' notes on the campaigns of Alexander the Great. These notes indicate that the reaction of Sillyon's residents to Alexander was hostile, in contrast to that of Perge, and that they defended themselves from a strong position, relying on mercenaries as well as soldiers. In any case it appears that Sillyon had been a military base since Persian times; the remains of buildings and fortifications from the Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine and Seljuk epochs reveal that the city preserved its military character for a long time.

Climbing a simple path from Yanköy toward the hill, the first thing one encounters is the lower gate. Consisting of a horseshoe-shaped court with two rectangular towers. It is similar to Perge's Hellenistic gate in its plan and masonry. On this basis it has been dated to the third century B.C.

Because Sillyon is situated on a steep-sided hill, there was no need to surround the city with walls. It was only in the west and south-west sections where the incline is at its slightest, that walls, towers, and ramparts were erected. These exhibit painstaking stonework and considerable technical expertise.

The city's oldest ruins lie north-east of the main entrance

gate. The first structure one encounters here is a two-storey, high-walled building from the Byzantine era; although it is in good condition,

its function has not yet been ascertained. At the end of its lies one of

Sillyon's most important structures, a 7x55 metre palaestra of Hellenistic date.

On its west wall are ten windows of differing dimensions. A little further on is

a small Hellenistic building with an elegant door and carefully executed

masonry. The building's fame is derived from an inscription written on the door

in the local Pamphylian dialect. The inscription, thirty lines in length, is the

longest and most important document in this dealect known today. It is a pity

that a portion of the inscription was lost when a hole was made in the door at a

later date. While the dialect, written in Greek characters, was used in a large

part of Pamphylian until the first century A.D., it was gradually forgotten

after that date and was replaced by Greek.

high-walled building from the Byzantine era; although it is in good condition,

its function has not yet been ascertained. At the end of its lies one of

Sillyon's most important structures, a 7x55 metre palaestra of Hellenistic date.

On its west wall are ten windows of differing dimensions. A little further on is

a small Hellenistic building with an elegant door and carefully executed

masonry. The building's fame is derived from an inscription written on the door

in the local Pamphylian dialect. The inscription, thirty lines in length, is the

longest and most important document in this dealect known today. It is a pity

that a portion of the inscription was lost when a hole was made in the door at a

later date. While the dialect, written in Greek characters, was used in a large

part of Pamphylian until the first century A.D., it was gradually forgotten

after that date and was replaced by Greek.

At the southern edge of the plateau one encounters a sad scene. The Sillyon theatre and the odeon beside it, described as being in an excellent state of preservation in the 1884 Pamphylian travel notes of the Austrian researcher Lanckoronski, disappeared down the hill in a landslide in 1969; only eleven rows of seats from the cavea were left in place.

Immediately after the theatre, rock-cut stairs with balustrades along the sides lead to Hellenistic houses of square or rectangular plan constructed in the meticulous stonework typical of that period. Going east, one sees a small Hellenistic temple. Rising above a podium measuring 7.30x11.00 metres, the temple's cella wall and stylobate are still standing. According to existing architectural remains, the temple was of the Doric prostyle type.

From the beginning of the thirteenth century the Seljuks settled in Sillyon in small groups, just as they did in certain other cities. In accordance with their custom they built a small, thin-walled, crenelated citadel on the acropolis. The most interesting building that has survived from the Seljuk period is a square, domed mosque in the north-west part of the acropolis.

Other than a few Byzantine and Seljuk buildings there are no important remains at the eastern end of the acropolis. On returning to the village from the upper gate, one passes a necropolis area consisting of simple graves, before arriving at a well preserved tower. Square in plan, the tower has two floors, with a door opening into the lower one. Doors on the upper level placed there for defensive purposes open onto the ramparts. The stadium is on a terrace south-west of the tower. It is in very poor condition; all that remains are the tiers of seats mounted on vaults running along its western length.

There could not have been enough springs in the area to ensure an adequate water supply, since it is clear that importance was given to the construction of covered and open cisterns from the Hellenistic period onward.

SIDE

Side,

ancient Pamphylia's largest port, is situated on a small peninsula extending

north-south into the sea.

Side,

ancient Pamphylia's largest port, is situated on a small peninsula extending

north-south into the sea.

Strabo and Arrianos both record that Side was settled from Kyme, city in Aeolia, a region of western Anatolia. Most probably, this colonization occurred in the seventh century B.C. According to Arrianos, when settlers from Kyme came to Side, they could not understand the dialect. After a short while, the influence of this indigenous tongue was so great that the newcomers forgot their native Greek and started using the language of Side. Excavations have revealed several inscriptions written in this language. The inscriptions, dating from the third and second centuries B.C., remain undeciphered, but testify that the local language was still use several centuries after colonization. Another object found in Side excavations, a basalt column base from the seventh century B.C. and attributable to the Neo Hittites, provides other evidence of the site's early history. The word "side" is Anatolian in origin and means pomegranate.

Next to no information exists concerning Side under Lydian and Persian sovereignty. Nevertheless, the fact that Side minted its own coins during the fifth century B.C. while under Persian dominion, shows that it still possessed a great measure of independence.

In 333 A.D., despite its strong land and sea walls, Side surrendered to Alexander the Great without a fight.

For a long period following the death of Alexander, Side came under the dominion of the Ptolemaic and Seleucid Empires, and in 190 B.C. witnessed a great naval battle. This encounter took place between the fleet of Rhodes, acting with the support of Rome and Pergamum, and the fleet of Antiochos III, the king of Syria, under the command of the famous Carthaginian Hannibal. Side took the side of Hannibal, but the Rhodian forces carried the day.

In the second century B.C. Side was able to stave off the forces of the Attaleids of Pergamum and preserve its independence, becoming a wealthy commercial, intellectual, and entertainment centre. Side's importance in the Eastern Mediterranean as an educational and cultural centre can be gauged by the fact that Antiochos VII, who ascended the throne of Syria in 138 B.C., was sent to Side in his youth to receive has education.

In the first century B.C. misfortune overtook Side in the form of Cilician pirates, who seized the city and turned it into a naval base and slave market. The people of Side seem to have tolerated the pirates because of the highly profitable nature of this commerce, which, however, gave the city a bad name in the region. Stratonicus, a man famous for his retorts and witticisms, answered the question, "Who are the worst, most treacherous people?" saying, "In Pamphylia the people of Phaselis, but in the whole world the people of Side". The famous Roman general Pompey ended the reign of the pirates in 67 b.C. and Side, by erecting monuments and statues in his honour, tried to erase its bad name.

Under Roman rule, Side prospered during a second golden age, especially in the second and third centuries when it became a metropolis ,seat of the provincial governor and his administrative staff. Due to its large harbour. Side in this era enjoyed commercial relations throughout the Mediterranean particularly with Egypt. Imported goods left Side for central Anatolia by road. Side's importance as a commercial centre can be ascertained by the hundreds of shops occupying not only the main streets, but also the narrowest of side streets and alleys. At the same time it continued as an important slave trading centre. Documents from the Imperial Roman period found in Egypt report that these slaves were sent to Side mainly from Africa. It is also known that Side possessed a large commercial fleet which did not pass up opportunities to commit piracy. Maritime commerce was the origin of the wealth of many merchants. These wealthy men did not work solely to increase their fortunes, but also provided for activities benefiting the people of the city, donating large sums to organize competitions and games, as well as to beautify the city and create social and religious organizations. One inscription found above a late period gate reports that two people, whose names cannot be made out, had a deipnisterion or soup kitchen erected for the use of government employees and the council of elders. A woman named Modesta organized gladiatorial events; Tuesianos, another inhabitant of Side, organized a feast to celebrate the return of the seamen to Side; and a husband and wife pair of philanthropists provided for the repairs of Side'' water system out of their own pockets. A great proportion of the buildings and monuments still standing at Side date to this magnificent epoch.

Side's last years of plenty occurred in the fifth and sixth centuries A:D. when it served as the seat of the Bishopric of Eastern Pamphylia. At this time there was much consturction, and the city expanded beyond the extant city walls. Starting in the middle of the seventh century, destructive raids by Arab fleets on the southern coast of Anatolia transformed it into a war zone. Side was naturally, affected, and excavations have uncovered ashy burnt layers showing that the city was entirely burnt by Arabs.

According to the twelfth century Arab geographer Idrisi, Side was at one time a large and populous city, but after being sacked it was abandoned by its inhabitants, who moved to Antalya, two days' journey away; as a result, according to Idrisi, Side became known as Old Antalya.

In order to protect itself from threats coming by land or sea, Side was

surrounded on all four sides by high walls. The sea walls have been much altered over the centuries due to repair and rebuilding and

have most much of their original appearance; they have even collapsed in several

places. By contrast, the land walls and their towers are almost whole, due to

their having been carefully constructed of conglomerate stone. The city is

entered through two gates in the eastern fortification wall. The large main gate

was built during the Hellenistic period. It is flanked by two towers and gives

onto a horseshoe-shaped courtyard. After passing through the courtyard and a

square room, one enters the city. As is the case in Perge, the gate and

courtyard complex were ornamented with many storeys of columns in the second

century A.D. and transformed into a ceremonial place of honour. The second

largest city gate, also belonging to the Hellenisitic period, lies on the

north-east of the city; behind its square towers lies a courtyard that is also

square in form.

walls have been much altered over the centuries due to repair and rebuilding and

have most much of their original appearance; they have even collapsed in several

places. By contrast, the land walls and their towers are almost whole, due to

their having been carefully constructed of conglomerate stone. The city is

entered through two gates in the eastern fortification wall. The large main gate

was built during the Hellenistic period. It is flanked by two towers and gives

onto a horseshoe-shaped courtyard. After passing through the courtyard and a

square room, one enters the city. As is the case in Perge, the gate and

courtyard complex were ornamented with many storeys of columns in the second

century A.D. and transformed into a ceremonial place of honour. The second

largest city gate, also belonging to the Hellenisitic period, lies on the

north-east of the city; behind its square towers lies a courtyard that is also

square in form.

The main street starts from this north-eastern gate and stretches all the way to the peninsula's western tip in an almost completely straight line. Along this street lay the city's principal official buildings and its squares. Excavations have revealed a perfectly planned sewer system. This system, covered with vaults, lay under the main street as well as the smaller streets.

Outside the city wall and opposite the main gate lies the nymphaeum, a monumental fountain consisting of a richly ornamented facade with three niches and with a fountain in front. Piped-in water used to flow from spouts in the middle of these niches.

The agora, the city's centre of commercial and cultural activity, lay along an arcaded street. It can be entered today from immediately opposite the museum. This square space was surrounded on all four sides by porticoes. Rows of stores can still be observed running behind the north-east and north-west porticoes. An interesting vaulted building lies in the agora's south-west corner adjacent to the theatre, this served as the city's latrium or public toilets and is the most highly ornamented and best preserved example in Anatolia. Sewers carried away the waste from this establishment, which had a 24-toilet capacity, while in front of the building ran a channel carrying only purified water.

In the middle of the agora lay a circular temple dedicated to Tyche (Fortune). All that is left today is the podium of this structure, but originally twelve columns ran around its exterior and the temple was topped by a pyramidal roof.

This agora was linked to a second, state agora by a street running along its southern edge. This agora, too, was square in plan and was enclosed by porticoes of lonic columns. It is believed that the high platform in the middle of the agora was used for the display and sale of slaves. Behind the eastern portico lay a large ornamented three-chambered building which, due to its architectural peculiarities, is thought to have been either an imperial palace or a library. From extant remains it can be ascertained that the building was originally two storeys and richly adorned with statues. Aside from a statue of Nemesis, which has been left in place to recall the original decorative style, all the statues found during excavation have been removed to the Side Museum.

The agora bathhouse, today used as the museum, is a five-room Byzantine structure dating to the fifth century A.D. It is entered through two arched doorways. The first room, possessing a small cold water pool, was the frigidarium. From here one passes to a stone-domed sweating room or lokonicum. The third and largest of the structure's rooms is the hot room or caldarium. The bath's heating system ran beneath the marble flooring. From the caldarium one can enter the two-room tepidarium or washing area through a narrow door. In front of the bath was a palaestra with a porticoed courtyard where men could excercise before bathing.

Next to the triumphal arch, which at a late date was used a city gate, lies a beautiful monument, partially restored in recent years. This monument consists of a niche between two aedicules and, according to an inscription found in the architrave, was built in 74 A.D. in memory of the Emperor Vespasion and his son Titus. During the construction of the late period city wall in the fourth century A.D., this monument was brought here from elsewhere in the city and turned into a fountain.

The theatre is the only extant example of its plan and construction type to be fount in Anatolia. It was erected in the second century A.D. on Hellenistic foundations. Because Side is virtually flat, the theatre's upper banks had to be built into the only natural rise available, which is not very steep, while the lower banks of seats overlay an arched substructure. Twenty nine seating levels can be counted below the 3.30 metre-wide diazoma, which divides the cavea in two. In the upper section only twenty two of the original twenty nine rows survive. Thus, this was Pamphylia's largest theatre and had a seating capacity of 16-17.000 people. In the outside gallery of the lower section, staircases rose to the diazoma. From interior galleries, staircases ascended to the theatre's upper section. The galleries' two ends probably contained paradoses, enabling them to be used as entrances for theatre staff and actors.

The orchestra was slightly larger than a semicircle, and at a late date it was surrounded by a nigh thick wall that rendered inoperative the lowest banks of seats. This wall was covered with waterproof pink plaster which allowed the orchestra to be filled from time to time with water for reenactments of naval battles and other sports; it no doubt also served as a pit for displays of wild animal combat. These displays usually pitted predatory animals against one another or against gladiators. Sometimes even unarmed people-criminals, slaves, and prisoners-were set against wild animals, and their helpless struggle was followed with rude glee.

A stage building rose off a wide podium behind the orchestra. It consisted of a two-storey facade 63 metres in length. On the podium, five narrow doors linked the orchestra ornamented with coloumns, niches and statues, and its lower storey contained five alrge openings allowing for the actors, and its entrance. Between these openings, just as in the theatre at Perge, were marble friezes illustrating Dionysiac themes. The stage building's reliefs have been transported to the agora for the duration of the restoration work which has newly begun is this area.

During the troubles of the fourth century A.D., a new fortification wall was built, and this wall took advantage of the high back wall of the stage building. During the fifth and sixth centuries A.D., the theatre was used as an open-air church, and the parados sections were decorated with floor mosaics and transformed into small chapels.

The most varied and beautiful temples in all of Pamphylia are to be found in Side. Two stupendous temples rose on the peninsula's southern point, right next to each other, the sea and the harbour. These temples were built in the second half of the second century A.D. Consisting entirely of marble, they are of the peripteros type and employ the Corinthian order. The short sides have six columns each, the long sides eleven. In the fifth century A.D. a large basilica was built in front of these temples, incorporating them into its atrium. Despite being heavily damaged, the temples' ancient configuration can be determined. Because Side's patron goddess was Athena, it is highly probable that one of the temples was dedicated to Athena, who in consequence, would have been featured extremely prominently as a protectress of the harbour and of sailors. As for the other temple, it must have been dedicated to Apollo. Restoration of the Temple of Apollo is ongoing.

Further on, to the east of the last big square off the arcaded street, lies a semicircular temple dedicated to the god Men. The cella of this temple was entered from the west by a staircase up the high podium. At the top of the stairs are four Corinthian columns. This temple dates to the end of the second century A.D.

Between the arcaded street and the theatre lie the remains of an early Roman temple. Of this temple, which is of the pseudo-peripteral type, only the podium remains. The podium remains is ascended from the north by seven steps. In front of the cella rise four granite Corinthian columns. Because of its proximity to the theatre, it is thought that this temple belonged to Dionysos.

Dating to the third century A.D., the biggest of Side's three public baths lies on the arcaded street. Its dimensions are 40x50 metres and it is a beautiful building in a fine state f preservation. Its various rooms are vaulted. The broad courtyard in front of this building was most likely used as a palaestra.

In order to satisfy their for a plentiful water supply, the people of Side went to almost superhuman lengths. Water from the head of the Melas river (today's Manavgat Çayı) reached Side after an adventuresome 30 kilometre journey on two-storeyed arched aqueducts, passing through channels carved out of cliffs, and vaulted tunnels and across valleys before it was collected in city cisterns, from which it was distributed in clay pipes.

Large cemeteries lie outside the city walls. In these cemeteries one can still see many types of graves, be they simple square holes, plain or carved sarcophagi, or magnificent memorials in the form of temples. These areas were called necropoli, cities of the dead. The most beautiful of these can be found in the western cemetery near the sea. On a podium reached by stairs rises a building shaped like a temple with four columns. Inside this building marble sarcophagi are situated in arched niches. This building dates to the second century A.D., and together with its ornamented courtyard must have served as the tomb of a wealthy family.

Side has been excavated by Turkish archaeologists since 1947, and excavations continue intermiltently.

![]()

Home | Ana

Sayfa | All About Turkey | Turkiye

hakkindaki Hersey | Turkish Road Map

| Historical Places in Adiyaman | Historical

Places in Turkey | Mt.Nemrut | Slide

Shows | Related Links | Guest

Book | Disclaimer | Send a Postcard | Travelers' Stories | Donate a little to help | Getting Around Istanbul | Adýyaman Forum

|

|