ANTALYA

The Map For Antalya and its surroundings

ANTALYA

The Map For Antalya and its surroundings

"The Turquoise Riviera"

Set amid amazing scenery of sharp contrasts, Antalya,

Turkey's principal holiday resort, is an attractive city with shady palm-lined

boulevards and a prize-winning marina. In the picturesque old quarter, Kaleici,

narrow, winding streets and old wooden houses abut the ancient city walls. Since

its founding in the second century B.C. by Attalos II, a king of Pergamon,

Antalya has been continuously inhabited. The Romans, Byzantines and Seljuks

successively occupied the city before it came under Ottoman rule.

At Antalya, the pine-clad Toros Mountains sweep down to the sparkling clear sea forming an irregular coastline of rocky headlands and secluded coves. The region, bathed in sunshine for 300 days of the year, is a paradise of sunbathing and swimming and of sporting activities such as windsurfing, water skiing, sailing, rafting, mountain climbing and hunting. If you come to Antalya in March and April, you may ski the mountains in the mornings and swim in the warm waters of the Mediterranean in the afternoons. Important historic sites and beautiful mosques await your discovery amid a landscape of pine forests, olive and citrus groves and palm, avocado and banana plantations. Perge, 18 km from Antalya along the east coast, is an important city of ancient Pamphylian. It was originally settled by the Hittites around 1500 B.C. The city features the remains of a theater and a handsome city gate.

Also east of Antalya, the town of Aspendos features the best-preserved theater of antiquity. The Aspendos Theater, with seating for 15,000, is still in use today. Nearby stand the remains of a basilica, agora and one of the largest aqueducts in Anatolia.

The Turquoise Coast is Turkey's tourism capital. Its full range of accommodations, sunny climate, warm hospitality and variety of excursions and activities make it a perfect holiday spot and popular venue for meetings and conference

The

Antalya Region, offering all the mysticism of past in our day, is now called the

"Turkish Riviera" due to its archaeological and natural beauties.

Antalya is the place where sea, sun, history and nature constitute a perfect

harmony and which also includes the most beautiful and clearest coast along the

Medditerranean. The city still preserves its importance as a centre throughout

history in the south coast of the country, in addition to its wonderful natural

beauties. The mythological city which housed the Gods and Goddesses now exhibits

all its secrets and marvels to mankind.

Antalya is located in the west of the Medditerranean region. In ancient times it covered all Pamphylia which means "the land of all tribes". The land really deserves the name since it has witnessed many successive civilizations throughout history. In 1st century BC the Pergamum king Attalus ordered his men to find the most beautiful piece of land on earth; he wanted them to find "heaven on earth". After a long search all over the world, they discovered this land and said "This must be 'Heaven' " and King Attalus founded the city giving it the name "Attaleia". From then on many nations kept their eyes on the city. When the Romans took over the Pergamene Kingdom, Attaleia became an outstanding Roman city which the great Roman Emperor Hadrian visited in 130 AD; an arch was built in his honour which is now worth seeing. Then came the Byzantines, after which the Seljuk Turks took over the city in 1207 and gave it a different name, Adalya, and built the Yivli Minaret. The Ottomans followed the Seljuks and finally within the Turkish Republic it became a Turkish city and an important port. Antalya has been growing rapidly since 1960 and its population is 1,146,109 acccording to the 1990 census.

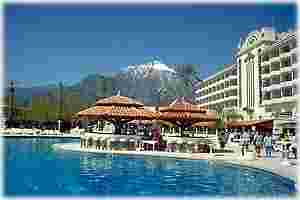

Kemer, Antalya |

Yivli Minaret, Antalya |

The climate of the province is typical Medditerranean: hot and dry in summers and temperate and rainy in winters. Sunshine is guaranteed from April to October and the winters are pleasantly mild. The humidity is a little bit high, about 64%, and the average water temperature is 21.5 °C. Antalya is really a heavenly place where the summer season is about 8-9 months long.

Transportation

You may reach Antalya from almost every city of the country, and even from little towns, coach companies going to Antalya are available.

Antalya has an international airport which may connect you to major cities. It has modern facilities including waiting rooms, restaurants, cafebar, and a shopping centre.

When traveling by sea, one can use the AntalyaVenice Ferryboat line.

Touristic Attractions

Antalya and its surrounding is an important and noteworthy touristic centre on the Mediterranean Coast with its perfect climate and splendid harmony of archaeological, historical and natural beauties, throughout the year. Daily tours to surrounding touristic areas like Side, Alanya and Termessos are available, in addition to longer tours to Pamukkale or Cappadocia or anywhere you would like to go. Proffessional tourist guides are also available.

Sightseeing

City Walls: The memorial Hadrian Arch and The Clock Tower are remarkable and date back to Hellenistic era.

Kaleici: This is the nucleus of a city which embraced many civilizations during time. It is now restored and has became a most attractive touristic centre with its hotels, restaurants, shopping and entertainment facilities. Kalei,ci retains all the original ancient Turkish archaeological characteristics. The port's marina has been completely restored and is wellworth visiting. The restoration activities in Kaleici won the Golden Apple Prize, the Oscar of tourism.

Antalya Museum: A prize winning museum and one of the most notable archaeology museums, of the world. It is also the only museum in Turkey with a children's department exhibiting ancient monuments appealing to children.

Hadrian's Gate: This ornamental marble arch was constructed in 2nd century BC by the Romans in honour of the Emperor Hadrian. It is the most amazing area in the whole ancient Pamphylia region.

Kesik Minaret (Broken Minaret): Once a Byzantine Panaglia church, later converted into a mosque.

Yivli Minaret: This fluted minaret of 13th century was built by the Seljuks. Decorated with dark blue and turquouise tiles, the minaret eventually became the symbol of the city.

Karatay Medresesi, Hidirilk Tower, Ahi Yusuf Mescidi, Iskele Mosque, Murat Pasa Mosque, Tekeli Mehmet Pasa Mosque, Balibey Mosque, Musellim Mosque, Seyh Sinan Efendi Mosque and Osman Efendi Mosque are other places to be visited.

"Han"s are Seljuk or Ottoman inns which have architectural significance. Some worth visiting are the Evdir Han, Klrkoz Han, Alara Han and Castle and Sarapsu (Serapsu) Han.

Ancient Cities

Termessos: It is a Pisidyan city with remnants of an agora, theatre and an odion. It has a reputation of being the most magnificent necropolis on the Mediterranean, 35 kms northwest of Antalya.

Perge: 18 kms northeast of Antalya. The ruins are spread on two hills, the theatre on one and the acropolis on the other. According to the legend the city was built by three heros from Troy.

Sillyon: 34 kms from Antalya on the Alanya direction. It is situated between Aspendos and Perge and dates back to 4th.century BC.

Aspendos: One of the most important Pamphilian cities. It is situated on the point where the Kopru River meets the sea. Once an important port and a commercal centre, it has a reputation for raising the best horses on earth. The odeon, basilica, galleria and fountains are worth seeing.

LIMYRA (TURUNCOVA, ZENGERLER)

According

to tomb inscriptions, Limyra was first known as Zemu-ri, a Lycian name. It is an

ancient Lycian site dating back as far as the fifth century B.C.

According

to tomb inscriptions, Limyra was first known as Zemu-ri, a Lycian name. It is an

ancient Lycian site dating back as far as the fifth century B.C.

It is thought that the Lycian prince Pericles, who opened war against the Persian administration and Greek colonies in the area with the aim of establishing a Lycian federation, selected Limyra as his capital around 380 B.C. In recent years German archaeological excavations have uncovered a magnificent heroon of Pericles.

Coins of the League type minted by Limyra provide evidence that it had become an autonomous city with membership in the Lycian League, by the second century B.C.

Limyra followed the mainstream of Lycia's history, coming under Roman domination in the first century B.C. and undoubtedly reaching its height during the Pax Romana.

Pliny explains that, in Limyra there was an oracular spring whose fish answered questions about the future. If the fish ate when food was thrown to them, the oracle was favourable, but it they flicked their tails and swam away, the reply was adverse.

Another interesting conclusion that can be made from inscriptions is that, in Limyra, counter to Lycian tradition as a whole, Zeus must have been worshipped on a large scale, and events like festivals and races were arranged in his name.

The ruins of Limyra are spread out across a plain and the surrounding rocky slopes, which widen like triangles as they descend southward from the hills of Mount Tocak. The first building one encounters here, just at the foot of the hill, is a theatre of medium size in a good state of preservation. Its cavea, divided in two by a diazoma, has sixteen tiers of seats below and more than sixteen above, though the exact number has not been firmly fixed. At the ends of these tiers are vaulted galleries, typically Roman in character, that take the form of semicircles which open onto the diazoma. The real entrances to the vaults are located on both sides of the diazoma. The stage building is too ruined to provide any idea of its original appearance. Limyra's theatre must have ben damaged in the major earthquake that occured in 141 A.D., since after the quake it was rebuilt with 20.000 denarii in aid from one Opramoas of Rhodiapolis.

Side by side on a level area to the south of the theatre are two separate settlement sites, almost like separate fortresses, each surrounded by walls of a different period. In the western enclosure in the partially submerged cenotaph of Gaius Caesar, Iying, north-east of a temple. Gaius Caesar, the adopted heir of Augustus, was wounded in the course of a battle he was waging in the east in 3 B.C. and died in Limyra on his way back to Rome. Because of this a tomb was erected in his memory here. Tower-like in form, it reflects the architectural character of its time. Unfortunately, very little of this cenotaph has survived to the present day. It was almost totally destroyed when fortification walls were constructed on top of it during the Byzantine period. The eastern walled enclosure is entered via a structure which can be seen.

Limyra, sor far as the variety of its tombs is concerned, is one of the

foremost cities in Lycia. The stone tombs and sarcophagi scattered in several groups mostly on the

slopes of Mount Tocak, are among the best known works of Lycian art. One of the

most outstanding of these is the Xntabura Sarcophagus immediately north-east of

the theatre. This is a three-part tomb consisting of a high base, on top of

which is the polygonal body of the sarcophagus covered with a gothic type

rounded lid. Two opposing sphinxes are depicted on the facade of the lid and a

sacrifice scene on the hyposoriun. These characteristics date the sarcophagus to

the fourth century B.C. In the eastern and western necropoli, the majority of

tombs are inscribed in Lyican and are made in the form of houses or lonic temple

facades that show traces of Greek architecture.

Lycia. The stone tombs and sarcophagi scattered in several groups mostly on the

slopes of Mount Tocak, are among the best known works of Lycian art. One of the

most outstanding of these is the Xntabura Sarcophagus immediately north-east of

the theatre. This is a three-part tomb consisting of a high base, on top of

which is the polygonal body of the sarcophagus covered with a gothic type

rounded lid. Two opposing sphinxes are depicted on the facade of the lid and a

sacrifice scene on the hyposoriun. These characteristics date the sarcophagus to

the fourth century B.C. In the eastern and western necropoli, the majority of

tombs are inscribed in Lyican and are made in the form of houses or lonic temple

facades that show traces of Greek architecture.

Other of Limyra's ruins are situated in the acropolis at an elevation of 200-300 metres up the slopes of Mount Tocak. In the acropolis, which consists of a keep and the Byzantine church, is a fourth century B.C. heroon built in the name of Prince Pericles. The upper portion, which is almost totally destroyed, has been partially repaired with sculptural and architectural fragments excavated among the tombs. One tomb, built on a terrace carved from the living rock, is similar in plan to the memorial erected to the Xanthos Nereids. Friezes on the east and west faces of the 3.40 metre-high hyposorium, show crowded scenes of men going to war on foot, on horseback, and in chariots. The real upper building, in addition to being in the form of an amphiprostyle temple, employs four caryatids in place of the columns seen on the north and south sides. The caryatids, standing on the base, support the architrave with their heads. The figure of a running woman appears on each corner of the north acroterium of the pediment, which was found in excavations of the heroon; at the centre is Perseus, holding the Gorgon's head in his right hand. These sculptures of the acroterium are now in the Antalya Museum.

OLYMPOS (FINIKE)

Olympos is one of the six major cities that Strabo describes as having had three votes each in the Lycian League. It is certain that the city took its name from the 2377 metre-high Mount Olympos (Tahtalı Dağ) 15 km. to the north. Existing records and remains indicate that Olympos was founded in Hellenistic times, and that its people were of an ethnic make-up different from that of the Lycians. The oldest record we have of the city is its League coinage dating to the secont century B. C. While Olympos was an important city, having won the title of metropolis around the beginning of the first century B.C., the captain of the Cilician pirates, Zeniketes, who had taken control of the area, captured Olympos and used it as a base. After a war that lasted four years, one Servilius Vatia, who in 78 B.C. assumed responsibility for eradicating the pirates from the area, having surrounded the castle with Zeniketes inside, put it to the torch. As punishment for their alliance with Zeniketes, Olympos and Phaselis were expelled from the Lycian League, made subject to the Cilician state, and their entire treasuries were confiscated.

After half-an-hour's walk north-west of Olympos, one arrives at a hill about 300-400 metres in altitude. On top of it is a natural gas flame that has been burning for thousands of years. Described in some ancient sources as extraordinary and astounding, it is known today in the surrounding area as "Yanartaş" or "Burning stone". This unextinguishable flame is mentioned in Homer's epic poem The Iliad, as the spot where the heroic Bellerrophon killed the Chimaera, a firebreathing mythical beast with the head of a lion, the body of a goat, and tail in the form of a serpent. The only trace the monster left on the face of the earth was his fiery breath, which has continued to spew forth its flame for centuries.

The most beautiful of Homer's myths about Lycia he told to Glaucos, and is summarized as follows:

One day the famous Corinthian hero Bellerophon saw a winged horse flying in the blue sky. This winged horse, after galloping to and fro across the sky, shot like a streak of lightning down to one of the high mountain peaks overlooking Corinth and quenched his thirst in its springs. Bellerophon, overcome with admiration when he saw the horse, wanted to catch it, but his efforts were useless. Known by the name of Pegasus, this divine steed would not even allow the hero to touch him. Wanting very much to capture this mysterious animal, Bellerophon went to the Temple of Athena on the advice of an oracle, and passed the night threre entreating the goddess of wisdom to help him in this difficult task. He saw Athena in his dream and she said, "Awaken, Bellerophon. To capture Pegasus I have brought you this golden bridle. With it you will soften the rebellious creature and will be able to mount him."

As soon as he caught sight of the golden bridle, Pegasus' bad temper disappeared and he became gentle as a lamb. Bellerophon, delirious with excitement, jumped onto the divine steed and together they rose into the heavens. From that day forward, Pegasus remained the inseparable friend of the young hero.

Terrible ordeals however, lay ahead for Bellerophon. At one point he killed his brother, and to purify himself of his sins he left the city of his birth, going to Protions, the king of Tirynthe. As soon as Anteia, the beautiful wife of the king, laid eyes on Bellerophon, whom the gods had generously endowed with courage and beauty, her heart caught fire and she became slave to an unquenchable passion for him, but for all her beauty, for all her wiles and sweet words, she was unable to steal the trustworthy Bellerophon's heart. The virtuous youth, not wanting to betray her husband, rejected each of the queen's advances. Because of this, Anteia, fabricating a malicious accusation against him, said to her husband, "Oh Poitos, either die or kill Bellerophon, for he is a proven enemy".

These words greatly angered the listening king -to have a guest killed would be an affront to the gods and would displease his subjects. For this reason the king wrote a letter and gave it to Bellerophon, bidding him take it to lobates, his father-in-law and the king of Lycia. Not knowing the situation he was in, Bellerophon set out immediately on the road to Lycia. On the bank of the river Xanthos the king welcomed him with great ceremony. The feast lasted nine days and nine nights. On the tenth day lobates requested the letter brought by his guest. Reading it, he learned that Proitos wanted the dissolute youth killed for indecently propositioning lobates' daughter, but how could he kill a guest whom he had entertained for ten days? lobates, wanting both to avenge his son-in law and to get out of murdering his guest, gave Bellerophon the task of battling the monster called Chimaera. No one had been able to rout this huge beast that was terrorizing all Lycia and scorching its earth. This lion-headed, goat-bodied, serpent-tailed creature, spewing flames from its mouth, set fire to anyone who came near it, igniting fields when it blew out its breath and reducing towns and villages to ashes.

Bellerophon mounted Pegasus and soared aloft. When he met the Chimaera, he attacked it from the air, thrusting a long lead spear into its flame-throwing mouth. The lead melted from the heat, began to flow, and the terrible monster died. From that day to this the Chimaeira's fire has burned without cease in the hills of Olympos.

After this victory, lobates, still seeking Bellerophon's death, sent him to battle the Solymians, who lived in the vicinty of Termessos. Once again the youth returned victorious from his assignment. This time the king ordered him to battle the Amazons. When the dashing youth succeeded at this difficult task, too, lobates believed that Bellerophon had descended from the race of the gods and kept him in Lycia, making the youth his son-in-law.

Bellerophon, who up to this time had received the help of the gods, was carried away with pride at his accomplishments and tried to reach as far as the heights of Mount Olympos, but Zeus, resenting, the arrogance of the young man flying so happily into the sky on Pegasus' back, loosed a horsefly, to sting the winged steed. When the fly struck, Pegasus threw Bellerophon from his back into the void and continued on his way aloft. From then on the gods would no longer send the horse down to earth but shut him up in a tower.

Bellerophon himself fell back to earth. The famous hero who had vanquished the dread Chimaera now began to limp about with an air of exhaustion. As a result of his overweening pride at being such an important hero, he was cast into wretchedness, always grieving, always miserable. In the end he died alone in a corner like a nameless, unknown beggar.

Olympos was founded on the north and south sides of a valley formed by the Göksu River, which is born in the western hills and empties itself into the Mediterranean. The acropolis of the northern settlement is still quite covered with overgrowth, making it nearly impossible to distinguish and name the ruins hidden beneath. The most impressive building on the northern side as the cella door of a templum in antis in the lonic order, some 150 m. west of the river's mouth. On top of the door, which is 7.85 metres high, are two consoles. From an inscription on a statue base Iying in front of the door we learn that the temple was built during the reign of Emperor Marcus Aurelius (161-180 A.D.). North-east of the temple is a Byzantine bath consisting of a few compartments whose function is unknown.

In an effort to control the Göksu, which divided the city in two, the Olympos, laid high polygonal masonry walls on both sides of the river to form quays. In the Byzantine era a basilica was built on top of the southern quay, whose fine workmanship is of Hellenistic date. Further back are the remains of a colonnaded street 11 m. wide, Iying admidst the ruins of the buildings that once stood near it. To the south-east, in a spot near the sea, can be found the ruins of a four-chambered bath. Both the cavea, which is set into a natural slope, and the stage building of Olympos'theatre are in complete ruins. Vaulted paradoses and other remaining architectural elements date to Roman times. In the necropolis area, which stretches from the theatre up to the south-west end of the city, vaulted chamber tombs and sarcophagi predominate.

PHASELIS

Phaselis was founded in 690 B.C. by colonists from Rhodes. According to one version of its founding, on the colonists' arrival in the area their leader Lacios came across a local shepherd named Cylabros at this spot. Liking the place and deciding to settle there, Lacios asked the shepherd whether he wanted barley, bread or dry fish as payment for the land. Cylabros chose fish. Thereafter it was the custom among the Phaselisians to offer dry fish every year as a blessing for this strange shepherd. From this tale we can deduce that there was a settlement at Phaselis before the arrival of the colonists.

Following a two hundred-year period when it was under Persian rule, Phaselis was restored to independence by Cimon, an Athenian general in 449 B.C. Shortly afterward it entered the Athenian maritime federation known as the Delian League. In the course if its history, the city assumed a strange attitude toward the Lycians and had a political structure different from theirs.

In 333 B.C., after gaining control of Asia Minor, Alexander the Great conquered Phaselis along with the rest of Lycia. Alexander stayed for some time in the city, where he had been welcomed with enthusiasm on reaching Lycia, and according to some sources remained there throughout the winter. One of these sources gives the following account of his days in Phaselis.

The city is of stunning beauty, with three harbours, straight thorughfares, squares, and a theatre. The first place Alexander visited was the Temple of Athena, where Achilles' spear was preserved, and touched the weapon with excitement. In the course of one his evening strolls he saw the statue of the Phaselisian philosopher Thodectes, pupil of the famous Socrates. Taking garlands from the men beside him, he placed them on the statue. In this manner he showed his respect for philosophers.

After the death of Alexander the Great, Phaselis, like all of Lycia, came in turn under the rule of the Ptolemies and of Rhodes. Judging from the coins it minted, the city appears to have entered the Lycian League some time after it broke loose from foreign domination and regained its freedom.

Because of the absence of a strong authority at the beginning of the first century B.C. Phaselis, along with neighbouring Olympos and some cities in Pamphylia, fell into the hands of the Cilician corsairs under the command of Zeniketes. The pirates, who had control over the entire Mediterranean, were hindering Roman trade and capturing Roman ships. As the result of a major campaing however, the Roman commander. Servilius Vatia, cleared the area of pirates in 78 B.C. but because Phaselis was found to have been in collusion with the brigands and to have harboured them, it was expelled from the League in punishment and its treasury was confiscated.

Because of its exceptional situation on the Egyptian, Syrian and Greek, sea routes, Phaselis enjoyed a bright history, especially during the Roman period. The Emperor Hadrian visited the city in 129 A.D. and new monuments were built to commemorate the event.

The Phaselisians, who in large measure depended on maritime trade for their livelihood, made a bad name for themselves in the commercial world throughout antiquity. Demosthenes who describes them as "generally a very treacherous and pitiless people", goes on to say. "They are very cunning when seeking a loan, but before long they forget that they have borrowed. And when they are reminded of it, they easily find a thousand pretexts and excuses..."

When the famous harpist Stratonicus was asked which people were the most treacherous he replied, "In Pamphylia the Phaselisians, but in the whole world, the people of Side".

Phaselis again became the scene of looting and piracy during the third century B.C. In the following periods, it was unable to profit from sea trade because of Arab raids, and it soon lost its importance.

Like the other colonies we have seen, Phaselis was established on a peninsula, with its acropolis occupying the tip. The principal buildings are situated at the foot of the acropolis on a low area to the north and southwest. Almost all of the ruins that can be seen today belong to the Roman or Byzantine periods.

As Strabo states, Phaselis had three harbours. The best preserved of these is the main one, otherwise known as the military harbour, which fishing boats easily enter and leave even today. The walls, which surround the entire acropolis and continue even over the harbour's breakwater, leave only a 17 metre-wide mouth at the centre. At this entrance, the remains of guard towers can still be seen above the tips of the waves. The cordon constructed of cult conglomerate stone and the other foundations on top of it are in sound condition.

The avenue linking the main harbour to the southern port has a threepart layout. The central and principal street is paved with blocks of conglomerate rock and measures 225 metres long by 20-25 metres wide. Narrow raised pavements in the form of terraces and reached by stairs, line both sides of the street. Leaving the city centre, the road ends on the side of the southern harbour with a single-arched monumental gateway erected in the name of Hadrian; it is now in a state of ruin. The city's principal buildings line this street. South-east of the main harbour are the remains of the major bath, dated to the second century A.D... It is evident from an inscription on its facade that the square agora at the end of this bath dates from Hadrian's time. A small church of the basilica type was built inside the agora at a later date. The wide area in the south-west section is enclosed on the west by shops of square plan. An inscription on a door at the front dates the agora to the time of the Emperor Domitian (81- 96 A.D.). However in later periods the agora underwent many changes. On the street, facing the city square, is another building, a small bath complex.

The theatre, situated on the north-west slope of the acropolis, is approached by steps from the town square. In all probability it was rebuilt on the Roman plan in the second century A.D. on top of an earlier Hellenistic theatre. The cavea building, which is in quite a good state of preservation had an average capacity of 3,000 people. The partially preserved walls of the two-storey stage building indicate that it had five doors.

The aqueduct, which begins at a spring on the hill behind the northern harbour and extends as far as the agora, is today. Phaselis' best preserved and most impressive ruin.

Tombs and sarcophagi of the Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine eras are seen in the acropolis. There are many tombs in the form of a single vaulted chamber set atop a square foundation, particularly on the coast surrounding the northern harbour.

Excavations and restoration projects have been carried out in Phaselis since 1980 by a Turkish achaeological team.

TERMESSOS

Termesos is one of the best preserved of the ancient cities of Turkey. It lies 30 kilometres to the north-west of Antalya. It was founded on a natural platform on top of Güllük Dağı, soaring to a height of 1.665 metres from among the surroundig travertine mountains of Antalya, which average only 200 metres above sea level. Concealed by a multitude of wild plants and bounded by dense pine forests, the side, with its peaceful and untouched appearance, has a more distinct and impressive atmosphere than other ancient cities. Because of its natural and historical riches, the city has been included in a National Park bearing its name.

The double "s" in Termessos provides linguistic evidence that the city was founded by an Anatolian people Acording to Strabo, the inhabitants of Termessos called themselves the Slymi and were a Pisidian people. Their name, as well as that given to the mountain on which they lived, was derived from Solymeus, an Anatolian god who in later times became identified with Zeus, giving rise here to the cult of Zeus Solymeus. The coins of Termessos often depict this god and give his name.

Our first encounter with this city on the stage of history is in connection with the famous siege of Alexander the Great. Arrianos, one of the ancient historians who dealt with this event and recorded the strategic importance of Termessos, notes that even a small force could easily defend it due to the insurmountable natural barriers surrounding the city. Alexander wanted to go to Phrygia from Pamphylia, and according to Arrianos the road passed by Termessos. Actually, there are other passes much lower and easier of access, so why Alexander chose to ascend the steep Yenice pass is still a matter of dispute. It is even said that his hosts in Perge sent Alexander up the wrong path. Alexander wasted a lot of time and effort trying to force the pass which had been closed by the Termessians, and so, in anger he turned toward Termessos and surrounded it. Probably because he knew he could not capture the city, Alexander did not undertake an assault, but instead marched north and vented his fury on Sagalassos.

The historian Diodors has recorded in full detail another unforgettable incident in the history of Termessos. In 319 B.C., after the death of Alexander, one of his generals, a certain Antigonos Monophtalmos, proclaimed himself master of Asia Minor and set out to do battle with his rival Alcetas, whose base of support was Pisidia. His forces were made up of some 40,000 infantry, 7,000 cavalry, and included numerous elephants as well. Unable to vanquish these superior forces. Alcetas and his friends sought refuge in Termessos. The Termessians gave their word that they would help him. At this time, Antigonos came and set up camp in front of the city, seeking delivery of his rival. Not wanting their city to be dragged into disaster for the sake of a Macedonian foreigner, the elders of the city decided to hand Alcetas over, but the youths of Termessos wanted to keep their word and refused to go along with the plan. The elders sent Antigonos an envoy to inform him of their intent to surrender Alcetas. According to a secret plan to continue the fight, the youth of Termessos managed to leave the city. Learning of his imminent capture and preferring death to being handed over to his enemy, Alcetas killed himself. The elders delivered his corpse to Antigonos. After subjecting the corps to all manner of abuse for three days, Antigonos departed Pisidia leaving the corpse unburied. The youth, greatly resenting what had happened, recovered Alceas'corpse, buried it with full honours, and erected a beautiful monument to his, memory.

Termessos was obviously not a port city, but its lands stretched south-east all the way to the Gulf of Attaleia (Alanya). Because the city possessed this link to the sea it was taken by the Ptolemies. It is very surprising that a city which had stood up to the mighty aries of Alexander not forty years before would now accept the sovereignty of the Egyptians.

An inscription found in the Lycian city of Araxa yielde important information about Termessos. According to this inscription, in the 200's B.C. Termessos was at war for unknown reasons with the league of Lycian cities, and again in 189 B.C. found itself battling its Pisidian neighbour Isinda. At this same time we find the colony of Termessos Minor being founded near the city in the second century B.C., Termessos entered into friendly relations with Attalos II, king of Pergamum, the better to combat its ancient enemy Serge. Attalos II commemorated this friendship by building a two-storeyed stoa in Termessos.

Termessos was an ally of Rome, and so in 71 B.C. was granted independent status by the Roman Senate; according to this law its freedom and rights were guaranteed. This independence was maintained continuously for a long time, the only exception being an alliance with Amyntas king of Galatia (reigned 36-25 B.C.). this independence is documented also by the coins of Termessos, which bear the title "Autonomous".

From the main road, a steep road leads up to the city. From this road once can see the famous Yenice pass, through which wound ancient road that the Termessians called "King Street" as well as Hellenistic period fortification walls, cisterns and many other remains. King Street, built in the second century A.D. by contributions from the people of Termessos, passes through the city walls higher up and stretches in a straight line all the way to the centre of the city. In the walls to the east of the city gate are some extremely interesting inscriptions with augury by dice. Throughout the history of the Roman Empire, beliefs of this sort-in sorcery, magic, and superstition-were widespread. The Termessians were probably very interested in fortune telling. Inscriptions of this kind are usually four to five lines long and include numbers to be thrown with the dice, the name of the god wanted for soothsaying, and the nature of the prediction given in the counsels of that god.

The city Termessians where the principal official buildings are located lies on a flat area a little beyond the inner walls. The most striking of these structures is the agora, which has very special architectural characteristics. The ground floor of this open-air market place has been raised on stone blocks, and to its north-west five big cisterns have been hollowed out. The agora is surrounded on three sides by stoas. According to the inscription found on the two-storey stoa on the north-west, it was presented to Termessos by Attalos II, king of Pergamum (reigned 150-138 B.C) as proof of his friendship. As for the north-eastern stoa, it was built by a wealthy Termessian named Osbaras, probably in imitation of the stoa of Attalos. The ruins Iying to the north-east of the agora must belong to the gymnasium, but they are hard to make out among all the trees. The two-storey building consisted of an internal courtyard surrounde by vaulted rooms. The exterior is decorated with niches and other ornamentation of the Doric order. This structure dates from the first century A.D.

Immediately to the aest of the agora lies the theatre. Commanding a view out over the Pamphylian plain, this building is no doubt the most eyecatching in all the Termessos plain. It displays most clearly the features of the Roman theatre, which preserved the Hellenistic period theatre plan. The Hellenistic cavea, or semicircular seating area, is divided in two by a diazoma. Above the diazoma rise eight tiers of seats, below it are sixteen, allowing for a seating capacity of some 4-5,000 spectators. A large arched entrance way connects the cavea with the agora. The southern parados was vaulted at some later time, the northern has been left in its original open-air state. The stage building exhibits features characteristic of the second century A.D. A long narrow room is all that lies behind it. This is connected with the podium where the play took place, by five doors piercing the richly ornamented facade or scaenae frons. Under the stage lie five small rooms where wild animals were kept before being taken into the orchestra for combat. As in other classical cities, an odeon lies about 100 metres from the theatre. This building, which looks like a small theatre, can be dated to the first century B.C. It is well preserved all the way to roof level and exhibits the finest quality ashlar masonry. The upper storey is ornamented in the Doric order and coursed with square-cut blocks of stone, while the lower storey is unornamented and pierced by two doors. It is certain that the building was originally roofed, since it received its light from eleven large windows in the east and west walls. Just how this roof, which spanned 25 metres, was housed, has not yet been determined. Because the interior is full of earth and rubble at present, it is not possible to gauge either the building's seating arrangement or its capacity. Seating capacity was probably not larger than 600-700. Amid the rubble, pieces of coloured marble have been unearthed, giving rise to the possibility that the interior walls were decorated with mosaic. It is also possible that this elegant building served as the bouleuterion or council chamber.

Six temples of varying sizes and types have been accounted for at Termessos. Four of these are found near the odeon in an area that must have been sacred. The first of these temples is located directly at the back of the odeon and is constructed of truly splendid masonry. It has been proposed that this was temple of the city's chief god, Zeus Solymeus. What a pity, then, that apart from its five metre-high cella walls, very little remains of this temple.

The second temple lies near the south-west corner of the odeon. It possesses a 5.50x5.50 metre cella and is of the prostylos type. According to an inscription found on the still complete entrance, this temple was dedicated to Artemis, and both the building and the cult statue inside were paid for by a woman named Aurelia Armasta and her husband using their own funds. To the other side of this entrance, a statue of this woman's uncle stands on an inscribed base. The temple can be dated on stylistic grounds to the end of the second century A.D.

To the east of the Artemis temple are the remains of a Doric temple. It is of the peripteral type, with six or eleven columns to a side; judging from the size of it, it must have been the largest temple in Termessos. From surviving reliefs and inscriptions, it too, is understood to have been dedicated to Artemis.

Further to the east, the ruins of another smaller temple lie on a rock-hewn terrace. The temple rose on a high podium, but to what god it was dedicated is not known at present. However, contrary to general rules of classical temple architecture, the entrance to this temple lies to the right, indicating that it may have belonged to a demi-god or hero. It can be dated to the beginning of the third century A.D.

As for the other two temples, they are located near the stoa of Attalos belong to the Corinthian order, and are of the prostylos type. Also dedicated to deities who are as yet unknown, these temples can be dated to the second or third century A.D.

Of all the official and cult buildings to be found in this broad central area, one of the most interesting is in the form of a typical Roman period house. An inscription can be seen above the Doric order doorway along the west wall, which rises to a height of six metres. In this inscription the owner of the house is praised as the founder of the city. Doubtless, this house was not really that of the founder of Termessos. Maybe it was a little gift awarded the owner for extraordinary service rendered to the city. This type of house generally belonged to nobles and plutocrats. The main entrance gives onto a hall which leads through a second entrance to a central courtyard, or atrium. An impluvium or pool designed to catch rainwater lies in the middle of the courtyard. The atrium held an important place in the daily activities of houses such as this, and was also used as a reception room for guests. As such it was often ostentatiously decorated. The other rooms of the house were arranged around the atrium.

A street with wide, shop-lined porticoes ran north-south through the city. The space between the columns of the porticoes was often filled with statues of successful athletes, most of them wrestlers. The inscribed bases for these statues are still in place, and by reading them we can recreate the ancient splendour of this street.

To the south, west and north of the city, mostly within the city walls, there are large cemeteries containing rock-cut tombs, one is supposed to have belonged to Alcetas himself. Unfortunately the tomb has been despoiled by treasure hunters. In the tomb itself a kind of lattice work was carved between the columns behind the kline; at the top there was probably an ornamental frieze. The left part of the tomb is decorated with the depiction of a mounted warrior dateable to the fourth century B.C. ıt is known that the youth of Termessos, much affected by the tragic death of General Alcetas, built a magnificent tomb for him, and the historian Diodoros records that Alcetas did battle with Antigonos while mounted on a horse. These coincidences suggest that this is indeed the tomb of Alcetas and that it is he who is depicted in the relief.

The sarcophagi, hidden for centuries among a dense growth of trees south-west of the city, transports one in an instant to the depths of history ceremony, the dead were placed in these sarcophagi along with their clothing, jewellery, and other rich accoutrements. The bodies of the poor were buried in simple stone, clay, or wooden sarcophagi. Dateable to the second and third centuries A.D., these sarcophagi generally rest on a high pedestal. In the family tombs of the weatlthy on the other hand, the sarcophagi were placed inside a richly ornamented structure built in the shape of the deceased together with his lineage, or the names of those given permission to be buried alongside him. Thus the right of usage was officially guaranteed. In this manner the history of one specific tomb can be asertained. In addition, one finds inscriptins calling on the fury of the gods to prevent the sarcophagi from being opened and to scare away grave robbers. The inscriptions also state the fines meted out to those who did not conform to these rules. These fines, ranging from 300-100,000 denarii and generally paid to the city treasury in the name of Zeus Solymeus, took the place of legal judgements.

No excavations have as yet been undertaken at Termessos.

ARIASSOS

Ariassos was founded in a narrow rocky valley in the Taurus mountains to the north-west of Antalya. The earliest known coinage of Ariassos dates to the first century B.C. ; these coins have the head of Zeus on the obverse and on the reverse, a humped bull. Strabo mentions the city, calling it Aarrossas; it is known in other sources as Areassos and Ariassos.

Apart from a few ruined Hellenistic period walls, all the remains date to the Roman and Byzantine eras. The best preserved structure is the city gate, which takes the shape of a tri-partite triumphal arch, with the central arch higher and wider than the side arches. The arches spring off stone socles.

The site is entered via a colonnaded street running east-west from this gate. In Byzantine times, buildings of unknown function were erected on this street, entirely destroying its character. The nature of other principal buildings cannot be determined because they consist now of nothing more than heaps of stone.

The south and west ends of the valley served as necropoli. Funerary structures found here possess Pisidian characteristics, and generally consist of vaulted structures placed on a high podium. Here lie opened crumbling sarcophagi decorated with sword and shield motifs. The lids of the sarcophagi are shaped like rounde roofs.

SELGE

Selge was an important Pisidian city. It lies on the southern slopes of the Taurus in a naturally fortified spot difficult of access. It is reached by a forest road that climbs past cliffs, rivers, and small waterfalls, then passes over a Roman bridge. Thanks to its natural and historical treasures, it has been included in the Köprülü kalyon (Bridged Canyon) National Park.

According to Strabo, Selge's founder was Calchas, and it was later resettled by the Lacedaemonies (Spartans). The first settlement occurred during the Doric migrations which took place at the end of the second millennium B.C. and were connected with the Trojan War. The second settlement took place at the beginning of the seventh century B.C. together with the colonization of Rhodes. No inscription confirming this has come to light in the city, however and the idea that colonists would choose a place hard to spot from the coast and hidden in the mountains seems difficult to accept.

Selge was the first Pisidian city to mint coins. The silver staters minted in Selge starting in the fifth century B.C. conformed to Persian standards and exhibit a startlingly close resemblance to the coins of Aspendos, from which it is hard to differentiate them. On the observe of these coins are two wrestlers; on the reverse appear a figure using a slingshot and the city's name, written as Stlegiys of Estlegiys. These local names are linguistic proof that the Pisidian language, which was related to Luvian, a language we known to have been spoken in third millenium Pisidia ,was still in use in the fifth century B.C.

We do not possess any continuous account of the city's history. According to the sources, Selge, an ancient foe of Termessos, took up sides with Alexander the Great when he came here. Most likely Selge was at war with its neighbours almost all the time, due to the deep-seated and widespread tendency to bellicosity in this region. We learn of an interesting event connected with Serge, from Polybius. In 218 B.C. Selge and Pednelissos, another Pisidian city, were at war. Selge had a large population and was capable of fielding about 20,000 soldiers. At this time many Pisidian cities were allied to Selge, and so they besieged Pednelissos.

The people of Pednelissos appealed to Achaios, uncle of Antiochos III, king of Syria, for help, and he gave the task of lifting the siege to Garsyeris, one of his generals. Polybios relates the rest of the incident as follows. The people of Pednelissos appealed to Achaios for assistance. He in turn sent the trusted Garsyeris and 6,500 men as help, However, the people of Selge prevented Garsyeris' arrival by seizing the main passes and cutting off access to them. While marching from Millias to Kretopolis, Garsyeris heard the news that the passes had been closed, and turned home. The people of Selge too pulled back, returned to their houses and started the harvest. However, this was a ruse, because Garsyeris immediately returned, seized the pass of Kretopolis and, stationing a force there, moved into Pamphylia, entering into contact with the enemies of Selge at Perge. He received pledges of assistance from them. In the meantime the troops of Selge tried to recapture the pass held by Garsyeris'men, but they were unsuccessful. They continued to wage war against Pednelissos and did not lift the siege. Because Pednellissos was suffering from starvation. Garsyeris decided to try to smuggle 200 men into the town, each laden with a bag of wheat. However, this attempt was unsuccessful and everything fell into the hands of the Selgeans. Bolstered by their own success. Selge's troops took the offensive and attacked. Leaving only a small force around Pednelissos, they threw their full force against Garsyeris and soon thereafter had him pressed into a very tight corner. Garsyeris counterattacked the enemy's rear with his cavalry in a surprise raid and was victorious. At the same time the people of Pednelissos were freed, and they attacked what remained of the enemy. the Selgeans suffered a heavy loss of some 10,000 men. The remaining troops escaped to the city, but Garsyeris would give them no change. He immediately followed them, sealing the passes, and appeared outside Selge. Their spirit broken and suing for peace, the people of Selge sent out one of their leading citizens, Logbasis, as an envoy, but Logbasis, betraying the trust of his fellow citizens delivered Selge to Garsyeris, who immediately occupied the city. Garsyeris extended peace negotiations until the arrival of Achaios. When Achaious reached the city, using a trick devised by Logbasis, he called the citizens and guards to a meeting. While the citizens were in the meeting, Achaious, with Logbasis'help, was just about to seize Selge and the Temple of Zeus at the Kesbedion outside the city, when the trick failed. A shepherd saw the troops and spread the alarm. The Selgeans gathered just in time. First they attacked Logbabis'house, killing him, his sons, and all his men, then they rushed to the defence of the city. They even freed all the slaves. Achaios was driven out at great loss of life. Immediately following this, the Selgeans appealed to Achaios to come to terms, and so they made peace, with the proviso that Selge pay an initial amount of 400 telents, and subsequently 300 talents more, and that it free all the prisoners taken from Pednelissos. The Selgeans thus regained their lands and their freedom.

As can be seen, the pepole of Selge kept their freedom but had to pay a heavy price for it. That they were able to pay is proof of the city's prosperity.

Strabo praises the city's natural beauties, its fruitful orchards, its wide pastures and forests. He also reports that the inhabitants of Selge often travelled great distances. The main source of revenue for the city was its production of olives, wine, and medicinal plants.

With the founding of the Kingdom of Galatia in 25 B.C., Selge lost its independence for a time. However, under Roman rule, Selge enjoyed good relations. Right up until the breakup of the empire, it kept its independent status and would not concede its beloved lands to anyone. We also know by the frequent minting of coins until the third century that the city's economic life remained healthy. The Goths, who were settled in Phrygia by the Emperor Theodosius (379-395 A.D.) soon thereafter revolted, raping and pillaging throughout Asia Minor. In 399 A.D. Selge, too, was attacked by Goths under the leadership of Tribigild, but beat the enemy back. This show of force is proof that Selge had lost none of its former strength.

Selge lay on three hills surrounded by a fortification wall. This wall, of which a portion survives today, had seven main entrances and high towers spaced at intervals averaging 100 metres. The first ruin visible today is the Greco-Roman type theatre, which forms part of the modern day village of Zerk. The theatre's lower portion rests on a roücky slope. The horseshoeshaped cavea is cut by a diazoma dividing the theatre into 30 tiers of seats below and fifteen above. The first row immediately below the diazoma has kept its stone seats intact. This theatre had a seating capacity of about 9,000. Four separate entrances give onto the diazoma. In addition, vaulted paradoses running between the cavea and the stage also provide access to the theatre. The Roman period stage building survives today only as a heap of rubble. Its general outlines, however, can be made out; it had five doors and a colonnaded facade. It can be dated to the second century A.D.

Immediately to one side of the theatre one can trace the outlines of the opposing rows of seats belonging to the stadium, even though it is, on the whole, in a very ruinous state. It appears from the surviving portions that the stadium was in all likelihood a little smaller than average. There are also several surviving inscriptions recording victories in the stadium at Selge. Most of these competitions were local, but every four years a larger regional festival and competitions took place.

The remains of two temples can be found atop the highest hill to the west. It is more than likely that this is the Kasbedion mentioned by Polyios. In that case, the large 17x34 metre peripteral temple must have been that of the city's chief god, Zeus. As for the small temple with the templum in antis plan, this can be tentaviely assigned to Artemis on the basis of an inscription found nearby.

Behind this hill is a giant round cistern, built not only for rainwater, but also to hold water brought by a channel coming from the nort-west.

Between this hill and the other hills to the south-east, lie the other principal municipal buildigns. Here on an incline lie the extremely fragmentary remains of a very long porticoed street, a nymphaeum, and a bath.

On top of the hill to the south-east lie the remains of a large square plan agora enclosed on three sides. Attached to it is an apsidal basilica belonging to a later period.

The ruins of Selge which mostly date from the Roman period show that, especially in the 2nd century A.D. Selge was a wealthy and influential city.

Selge remains unexcavated.

![]()

Home | Ana

Sayfa | All About Turkey | Turkiye

hakkindaki Hersey | Turkish Road Map

| Historical Places in Adiyaman | Historical

Places in Turkey | Mt.Nemrut | Slide

Shows | Related Links | Guest

Book | Disclaimer | Send a Postcard | Travelers' Stories | Donate a little to help | Getting Around Istanbul | Adiyaman Forum

|

|